Namita is a yoga teacher, writer and artist based in India. She’s been teaching yoga for the last 13 years. A gold-medallist law graduate, she also has a Post-graduate Diploma in Intellectual property rights from National Law School of India University, Bangalore. She is currently an Artivist-in-Residence at ICAAD.

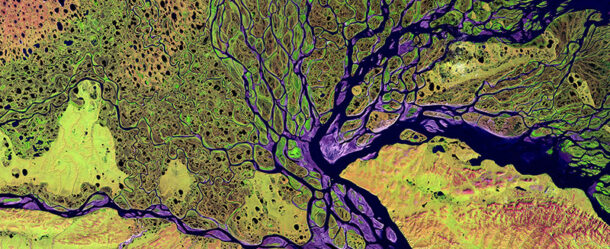

Her Artivism collection, Colonialism and the Climate Crisis, demonstrates how colonialism has been, and continues to be, the major cause of the climate crisis. The collection of paintings has received national acclaim in India and is now on view through our virtual gallery.

We asked Namita to share what inspired her new collection, what she hopes for the audience to take away from it, and what comes next for her as she continues to work towards advancing social justice through the arts.

What inspired your Artivism collection?

I’d been reading about colonialism as the cause of the climate crisis, and when I saw ICAAD’s call for artists to create art on any human rights topic, I thought of depicting the climate crisis as a human rights issue. Far too often, we see the climate crisis framed as a matter of carbon emissions that we can compensate or offset our way around. But the colonial dimensions of the climate crisis cannot be overlooked any longer. The culture of colonization – both historical and ongoing – is the context from which the climate crisis arises. I thought it would be interesting to create a series of paintings that make explicit the link between colonialism and the climate crisis, and also point to indigenous perspectives that dominant culture excludes. I’m thankful to ICAAD for trusting me with this project and giving me the creative freedom and support I needed to execute all these ideas.

What would you like the audience to take away from your work?

I would love for the audience to take away with them an inkling of possibilities of another way of life. That the current profit-over-people system we live under isn’t the only one to have ever existed. That another world is possible, one that is built on a people-over-profit paradigm. Indigenous cultures around the world have lived on the same land for thousands of years in relative harmony with the elements. While I’m not suggesting that indigenous wisdom is a silver bullet for all our woes, I would like to awaken in a viewer a bone-deep memory of a way of life that wasn’t centered on extraction and over-consumption, but on the interconnectedness of all life.

One idea I’ve expressed in the Apocalypse as Collapse-Renewal painting is that the seeds of renewal are within the collapse we see all around us, and it is for us to align with renewal in whatever ways we can. And also to recognize the colonizer inside each of us, in a culture that normalizes and celebrates exploitation as success. I was intentional in not taking the series toward a doomsday scenario as the cliff edge we are often said to be hurtling toward, with our fossil fuel dependence and the profit-over-people paradigm we live in. We need stories that point us to a whole other way of relating to the earth, not as a bunch of resources but as a web of relationships. And that our innate sense of awe and reverence for life stands in direct opposition to the colonizing impulse that has brought the climate crisis to our doorsteps. That is what I’ve tried to share with this series.

How did you first become interested in art? In art as a form of activism?

To me, the strange liberty of creation is itself a form of activism. It’s been the crack in the sidewalk that I’ve pushed my way through to feel a sense of aliveness and agency. I’ve been drawn to artistic expression for as long as I can remember. It was a way for me to know what was going on inside me, to reclaim agency, to heal, to turn pain into power. Creativity has been my most dependable spiritual practice. I’ve had my apprehensions about art as a form of activism, because I wondered how something that is so personal and “self-serving” could have any impact on the world outside me. How can paint on canvas be a tool for societal change? Does it even matter what I paint? The answers that came to me were that the role of art is to expand the capacity for feeling, empathy and curiosity. To expand a viewer’s sense of possibilities. Which is more important than one may realize. Also, what is most personal is often most universal.

I know that art has a way of making one stop and feel. It can awaken a bone-deep memory of something long forgotten, or affirm and articulate something you’ve always felt but never had the expression for. I’ve had people share really interesting interpretations of my art that I could not have thought of, and it seems clear to me more than ever that art is a verb. A conversation. As an artist, I throw a pebble in the lake of your psyche when I have you take in a painting. There’s no commanding or even predicting where the ripples lead you, but it sure is interesting to watch.

What role do the arts play in informing conversations around climate change?

The arts have a huge role in advancing conversations about climate change and climate justice. Giving people just the statistics and hard numbers about climate change can have the effect of numbing or alienating people from the issue. Whereas art provides a story, a container, a pause, a space to feel. It allows for and affirms our humanness in a dominant culture that is anti-human in so many ways everyday. It evokes our sense of interconnectedness with everything around us, affirming our personal connection to – and role in – the larger picture. With art that addresses climate change, my intention is to have a viewer see climate change not as some faraway headline for other people to deal with, but as an aspect of our own personal, troubled, grief-strewn relationship with the earth.

What comes next for you as an artist?

I’m working on a commissioned piece right now for someone’s new home here in Mysore. And I’ve also been planning a new series called “Who Does She Think She Is?” It will be a series of surreal portraits of people who identify as women answering the question that is often thrown at them to diminish them or make them doubt themselves. While intended to undermine a woman’s self-worth and question her autonomy and agency, it is also a really good question on its own, minus the misogynist underpinnings. A question that underlies every decision we make, how we move through the world, how we survive society, how we see ourselves and the value of our lives.

You can follow Namita on Instagram or visit her website.