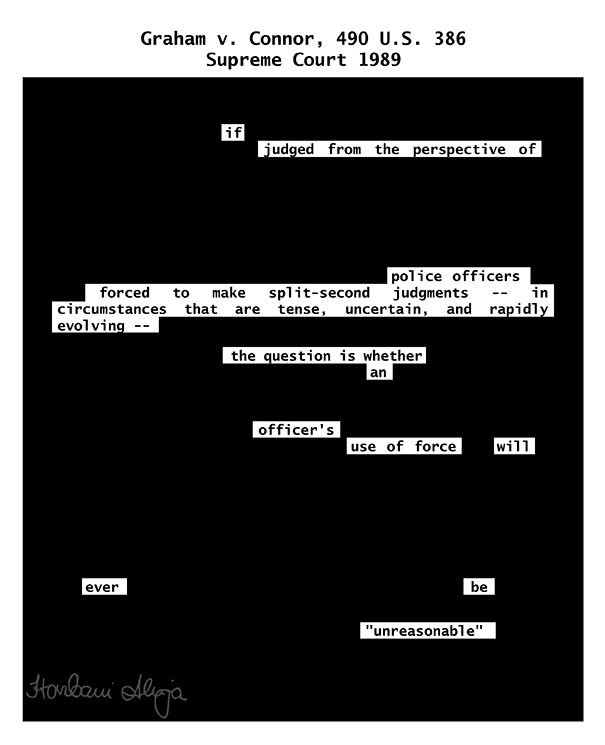

In 1989, Graham v. Connor again tested the possibilities for police accountability at the Supreme Court. The standard of “objectively reasonable” became the benchmark for police decision-making, but as Harbani highlights in her poem, “the question is whether an officer’s use of force will ever be ‘unreasonable.’”

With over 564 [as of July 10, 2021] police murders in 2021 alone, that question remains with human rights advocates. Convictions like that of Derek Chauvin are isolated cases that represent less than 2% of cases in which individual police officers face consequences for their brutality.

While electoral politics is far from the only arena in which change can and is happening, the Biden Administration seems to have learned nothing from the largest movement in U.S. history and the voters who delivered him the presidency.

Even with the House, Senate, and Presidency, establishment Democrats on the whole seem ready to kneecap themselves at any genuine demand for police accountability. It seems as if, after decades proving otherwise, we still seem to believe that police can hold themselves accountable despite the fact that the federal government has several tools at their disposal for holding institutions, like the police, accountable.

Funding is a great example. One of the demands for basic police accountability, proposed by the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, is the use of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

It enables the Justice Department to deny federal assistance to programs or activities that engage in discrimination, and it was used to enforce the Brown v. Board decision. This power already exists within the federal government and could be implemented to hold police departments accountable, with financial consequences if they fail to meet their obligations to protect their constituents.

“Part of our responsibility as human rights advocates is to remind one another what we deserve and what is and must be possible…”

To date, the Biden Administration has refused to use its real power to move this policy forward, or any other police accountability mechanism beyond repeating failed reforms under a facade of racial justice.

Even the straightforward request of establishing a national database for police misconduct has been ignored by the administration. At ICAAD, we see data as a crucial piece of human rights advocacy. It helps foster transparency, clarify the intricacies of a problem, and point to recurring patterns of structural discrimination. To date, NGOs like Mapping Police Violence have been picking up the slack to track the horrific state violence at the hands of police across the country.

Part of our responsibility as human rights advocates is to remind one another what we deserve and what is and must be possible — safety from those who claim to be ensuring public safety for all should not be a heavy lift. Settling for reform when the federal government has the power to actually make police departments sweat, even a little bit, over the civilians they kill, is just not good enough. It’s on us to demand better.

Read Police Cannot Police Themselves Part I: LA v Lyons (1983)