Mauri mauri. This exhibition tells the story of Rabi Island and the Banaban people, displaced from their island home in the Pacific over 70 years ago as a result of colonial mining and environmental destruction. Here, we highlight the resilience of the Banaban people as they preserve their culture and history amid protracted human rights struggles, and ask that you join us in taking action. #JusticeforRabi

Explore the Exhibit

- A Woven History of the Banaban People

- Interviews with Banaban Elders

- Artivism Works by Katja Phutaraksa Neef

- Ocean Island Untitled by Vaitoa Teaiwa Mallon

- Banaban Dance

- Handicrafts by Members of the Auckland Banaban Christian Trust

- Banaban People Leading the Way for Climate Justice

- Portraits on Rabi Island

- Join the Movement

Celebrating the International Day of the World's Indigenous Peoples - on Rabi and Beyond

Learn more about the artivism and commemorations taking place on Rabi this year.

The stories in this exhibition take us to the sea of islands and ocean states that are connected by generations of movement, struggle, and expansion in the Pacific, specifically the places of Banaba and Rabi.

The story of the displacement of the Banaban people and the dispossession of Banaba in the name of extractive industry carries important lessons for climate justice movements and Indigenous resistance.

From the early 1900s to the end of the 1970s, the British Phosphate Commission – jointly owned by the British, Australian and New Zealand governments – mined 90% of the Banaba’s surface.

This extractive practice left behind barren and uninhabitable land, resulting in the forced resettlement of Banabans to Rabi island in Fiji in 1945.

To this day, Banabans on Rabi Island face discrimination as a partially self-governing entity falling between the cracks of Fiji and Kiribati. For the few hundred Banabans that have remained on their home island, lack of access to clean water and food imports create persistent challenges.

Banaba is an island nation currently within the political boundaries of Kiribati in the northern Pacific. In 1945, the British Phosphate Commission relocated Banabans to Rabi Island in Fiji. Rabi has functioned as a semi-autonomous jurisdiction and secondary home for Banabans since.

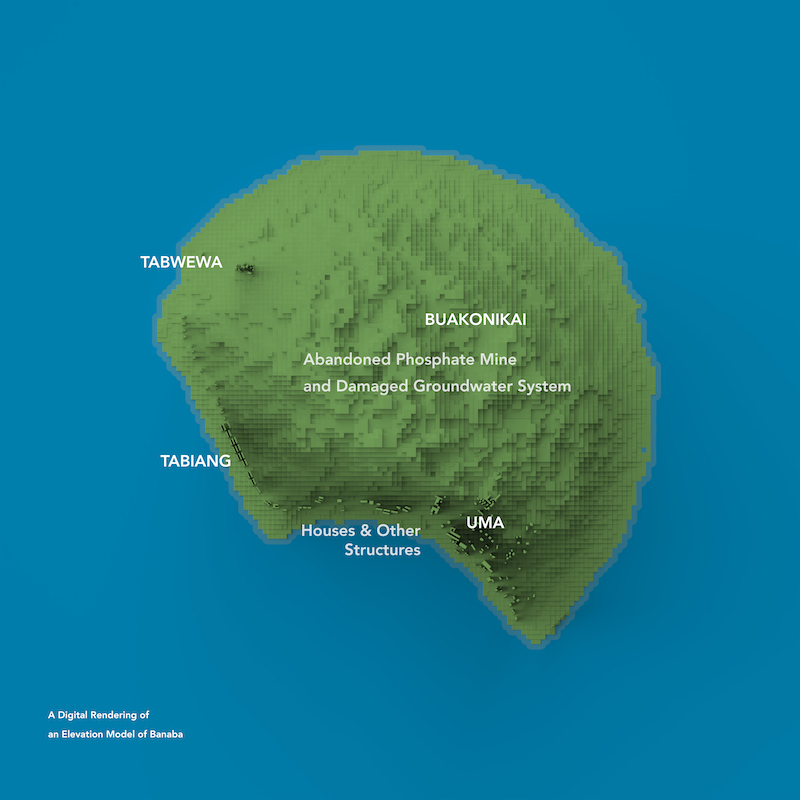

You’ll notice the Native and Indigenous place names on the map of the region. As shared by the mapmaker, David Garcia:

“Mapping is not only about representation but also about contestation. These works are aimed at supporting campaigns regarding raising awareness about extractivism and colonialism in the Pacific, particularly towards human rights and environmental justice in Banaba and Rabi.

Far from an objective representation, these maps are necessarily politicised images of the locations and landscape in the storytelling regarding Banaba’s and Rabi’s geography and history. After all, mapping is political because space, knowledge, and power are intertwined.

The politicisation of mapping and honesty about it can bring useful conversations for change.”

The map of Banaba, shown through a Digital Elevation Model (DEM), displays the effects of the mining and the current structures on the island.

22 million tons of land had been removed.

Ninety percent of Banaba’s surface had been stripped away.

The mining activities cut down the landscape from 80 meters above sea level to only 20-30 meters above sea level.

The damage is devastating, yet in sharing these stories we centre the legacy of resistance and the emergent desires, aspirations, and visions of the Banaban people.

“If Banabans think of blood and land as one and the same, it follows then that in losing their land, they lost their blood. In losing their phosphate to agriculture, they have spilled their blood in different lands. Their essential roots on Ocean Island are now essentially routes to other places.”

Teresia Teaiwa, 1998

“In the culture of my father’s people, te I-Banaba – there is no such thing as being part Banaban.

You either are or you aren’t Banaban.”

Teresia Teaiwa, 2014

Kioa Climate Emergency Declaration

In October 2022, powerful Pacific civil society advocates came together for the first time to draft and sign the first Kioa Climate Emergency Declaration. Unlike similar declarations, delegations came directly to communities on the frontlines of the climate emergency on Kioa Island. Kioa was purchased by Tuvaluans from the island of Vaitipu in 1947.

The gathering was just 15 kilometers from Rabi Island, where Banabans were forcibly relocated in 1945, and a delegation from Rabi attended and drew attention to issues of displacement and loss and damage. As opposed to holding high level dialogue overseas, the Declaration brought the conversation to the community: in the village hall, evacuation center, and into the very homes of Kioans.

Quote from the Kioa Climate Emergency Declaration 2022

Summary of the Priorities of Pacific Civil Society Based on the Kioa Talanoa 17-19 October 2022

“The history of the Banaba people is a lesson to the world. We were forcibly relocated by Australian, British and New Zealand governments from our island home in modern day Kiribati to an island in Fiji. Our relocation was a direct result of extractive industry and global trade. We bear testimony to the human cost and trauma borne by a community. We are what non-economic loss and damage looks like. We do not want any other community to go through what we experienced.”

“We can’t just keep telling the story of devastation and vulnerability over and over again.

Where does the crisis end, if not with justice?”

Katerina Teaiwa, 2021

Join the Movement

The British Phosphate Commission was jointly owned by the UK, Australian, and New Zealand governments. Join us in calling for justice, starting with the New Zealand government. Stand in solidarity with the Banaban people and add your voice to the petition.

Contemplate

We encourage you to explore the exhibit and share your reflections. Selected reflections will be shared as part of the exhibit.

We are grateful for the generous support from the New Zealand National Commission for UNESCO in putting together this virtual exhibition. The exhibition at Silo 6 in Auckland, New Zealand in February and March 2023 was supported by Creative NZ, the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy, Amnesty International, and the New Zealand National Commission for UNESCO.

About ICAAD Artivism