By David McDaniels and Jyoti Diwan

October 26, 2021

Solving homelessness must start with reframing the challenge from an economic burden or criminal issue to the human rights crisis it is.

“Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, and housing.”

In 1948 The United Nations General Assembly passed this article as a part of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It signified a commitment to treating homelessness as a human rights issue. Over 70 years later in the UN’s Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing, the General Assembly affirmed this commitment once again writing “homelessness is a profound assault on dignity, social inclusion and the right to life.” However, the gap between rhetoric and actual implementation is ever-increasing.

In the face of human rights doctrine, the misclassification of homelessness as an economic and criminal problem has persisted and grown in many settler-colonial, neoliberal countries, including the United States. Incarcerating and imposing monetary fines on those struggling to survive has become a quicker and short-sighted solution in place of social support. These short-sighted and cruel solutions force individuals into a criminal justice system that profits off of repeat offenders. This systemic abuse calls for an immediate overhaul.

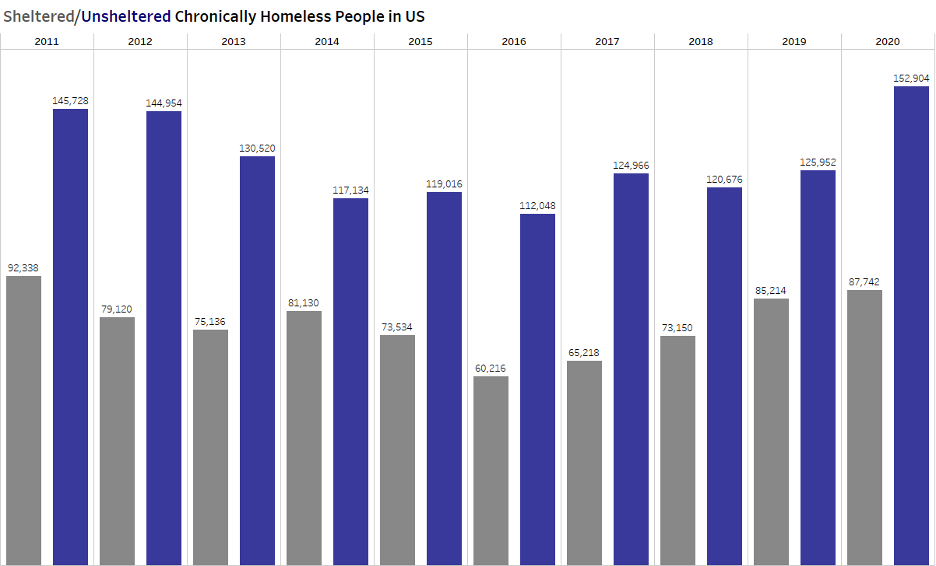

The treatment of unhoused individuals in the United States is particularly concerning. Over the past 5 years, the U.S.’s homeless population has grown to the point where “on a single day in January 2020, there were more than 580,000 individuals who were homeless. This growth has coincided with a 1300% increase in tent cities since 2007. As a result of these trends, the number of chronically homeless individuals, those who have been unhoused for over a year, has increased by over 15% in the last two years.

“Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, and housing.”

The governmental response to this rise has been to punish the victims. This decision has begun to push those experiencing episodic or occasional homelessness to become chronically homeless. In the last 5 years, sit-lie ordinances, which make it illegal to sleep or lie on public spaces such as sidewalks, have risen by 50%. They have been implemented in conjunction with anti-homeless architecture across U.S. cities. This includes additional armrests and bends in benches that previously served as places to sleep for the unhoused. Further, there has been a 40% increase in anti-panhandling laws, removing a primary source of income for the vulnerable population.

The crisis has been even further exacerbated by the pandemic. Homeless populations are rapidly growing as eviction moratoriums and rent forgiveness policies, enacted as COVID relief legislation, come to an end. A University of Washington study found that even in eviction-protected apartments, “if a landlord wants to evict a tenant and they’re really intent on doing it, they are probably going to accomplish it.” The study goes on to find that this process of “informal eviction” has had a large hand in the rise in the homeless population.

The increasing brutality toward unhoused individuals cannot be blamed on a lack of understanding or judicial precedent. The 9th Circuit Court ruled in Martin v. City of Boise that punishing unhoused individuals violates the 8th amendment, which protects against excessive fines and cruel and unusual punishment. Yet despite this ruling, supposedly “progressive” cities across the country have actively worked to repeal the decision and find loopholes. For example, one Los Angeles County supervisor said in protest of the decision that “[i]t’s critical we have access to every tool at our disposal to combat homelessness” referring to policies that were ruled to violate the 8th amendment. This immense effort to deny humanity-affirming change makes it all the more important to fight for solutions that prioritize addressing the root causes of homelessness.

“This immense effort to deny humanity-affirming change makes it all the more important to fight for solutions that prioritize addressing the root causes of homelessness.”

The first step in this process is to better understand said causes. Most notably, mental illness and government hostility are implicated in over 40% of the cases of homelessness. After the mass deinstitutionalization of mental health care in the 1970s and 1980s, state and local leadership failed nationwide to follow through to provide alternative housing options for these groups. Therefore, with cheap, single-room apartments becoming more and more scarce in cities, many were and still are forced to live in public spaces.

Another root cause in need of examination is homophobia and transphobia. Discrimination and abuse at home, work, and school have resulted in LGBTQ+ individuals making up a disproportionate number of homeless youth. The Williams Institute at UCLA found that while only around 10% of the general youth population identify as LGBTQ+ they represent 40% of the homeless youth population. Similar trends are seen with survivors of domestic violence. A 6-year study in Massachusetts found that 92% of homeless women had experienced physical or sexual assault. Not only are these survivors often forced from their homes in fear, but they struggle to find new places willing to rent to them. In 2005, a New York City study found that 28% of landlords plainly refused to rent to victims of domestic violence.

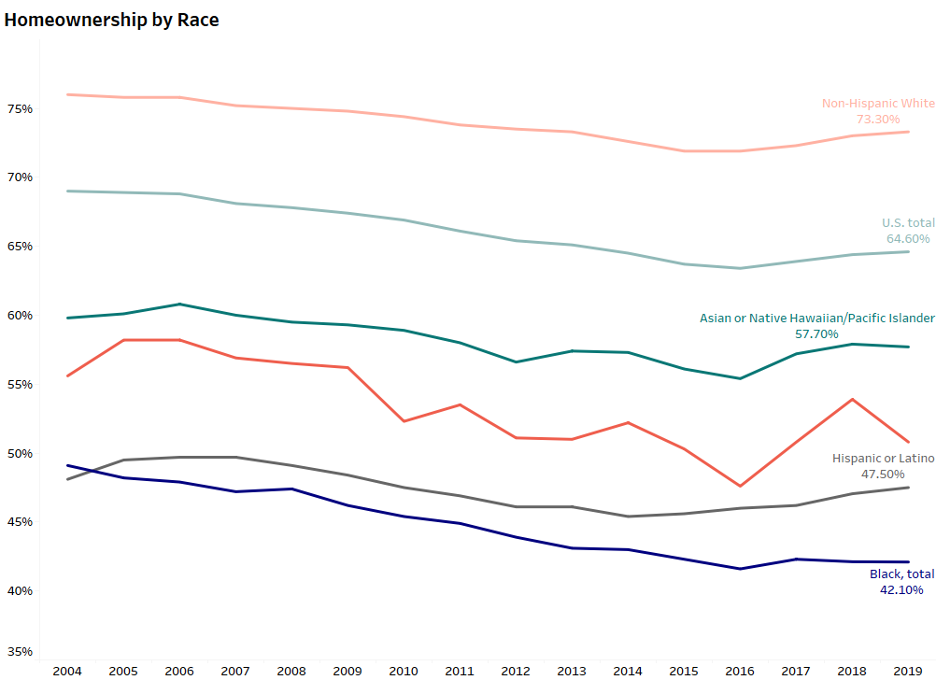

Race is also an important lens through which to view housing disparities and the consequent responses. Black Americans make up only 13% of the national population but account for over 39% of those experiencing homelessness. This massive gap is attributed to structural racism with examples including housing discrimination, unequal job opportunities, and cycles of racial violence. These root causes coupled with a weak social safety net further emphasize just how bleak the housing crisis is for vulnerable populations.

Still, the challenges do not end with discrimination and neglect; exorbitant housing prices exacerbate the issue even further. The National Housing Index showed a 13.2% increase in housing prices over the past year, the highest annual increase since 2005. This change has priced out many families from finding low-cost housing. Furthermore, even when affordable property does become available, real estate speculators often swoop in and hold them vacant until their price increases and they are able to gentrify the area. For example, in Oakland, California, there are 4 times as many empty houses as there are homeless people. In response to this, a group called Moms 4 Housing has attempted to repossess the empty homes as places for unhoused individuals to stay. This desperate reclamation of the property highlights just how little action the state has taken to fix the issue. In the face of all of this, modern housing policies make it extraordinarily difficult for even those with housing vouchers to find places to live. In a study by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, researchers found that only 14% of the families that receive housing vouchers use them. This is due to a lack of information provided on the process and a scarcity of qualifying units.

This plethora of root causes makes it clear that the failure to address homelessness is a human rights issue caused by governmental inaction and preference for investors over constituents. Failure for a government to provide adequate housing options places people at risk of premature and preventable death. Additionally, the inability to obtain a home address impacts rights to vote, work, and receive social benefits. These trends illustrate a system that consistently endangers the human rights of unhoused individuals.

“There is an opportunity to help solve this problem, but it starts with reframing homelessness from an economic burden or criminal issue to the human rights crisis it is.”

To make matters worse, the U.S. government not only fails to grant basic these rights but punishes those who then cannot obtain them. This injustice highlights a system in desperate need of widespread reform. This starts with strong legal advocacy to ensure that decisions like Martin v. City of Boise are upheld and enforced. More broadly, homelessness can no longer be governed through a solely economic lens. People are not objects of profit or loss, so their housing cannot be viewed as such. Cities must direct funds to provide affordable and reduced-price housing.

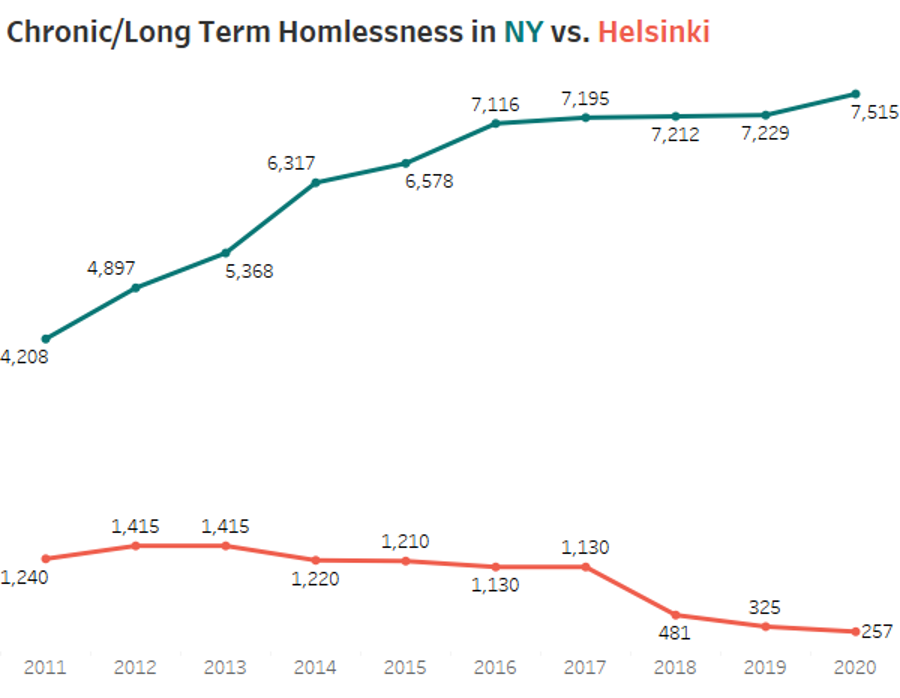

This type of change is possible. In fact, it has been done before — just not yet in the U.S. In 1987 Helsinki, Finland allowed a similar rise in homelessness to that of many U.S cities. They had over 18,000 unhoused individuals on their streets and needed a shift in policy. Instead of arresting or fining people, the government adopted a Housing First Policy. This means that the offer of a place to stay is unconditional and guaranteed regardless of status, condition, or reason. The system means that one “can pay rent through state housing benefits and can even opt to stay for the rest of their lives.” Helsinki treats the issue as one of basic dignity, and therefore, has been able to improve and save lives. Thirty years after the implementation, the homeless population in the city is at 6,000 and consistently shrinking despite population growth. Helsinki’s success provides a roadmap for U.S advocates and cities to adopt. There is an opportunity to help solve this problem, but it starts with reframing homelessness from an economic burden or criminal issue to the human rights crisis it is.

David McDaniels is an Intern at ICAAD and is a junior at Georgetown University from Westchester, NY. He is studying Government and Sociology while serving as president of the campus ACLU chapter.

Jyoti Diwan is a Data Analyst at ICAAD. She digs deep into large data sets to uncover solutions and provide the evidence for strategic decision making.