By David McDaniels

August 20, 2021

“In suites between man and man, the ancient trial by jury is one of the greatest securities to the rights of the people.”

Since 1788 in Virginia’s Bill of Rights, trial by jury has been established as a foundational pillar of modern democracy. It is sanctified because of its purity and simplicity. Twelve peers—not Congress, local leadership, or corporations— have the power to assess guilt. However, this pillar has not translated to justice for all. Throughout the 20th century, nothing prevented peremptory challenges of jurors because of their race or ethnicity. This often resulted in Black defendants not being judged by a representative group of peers but intentionally all-white juries. Simply, a trial judged by “peers” cannot be just when certain jurors are excluded because of their identity.

Had this been the end of Batson’s story it would have been just another in a long line of racial injustices in the U.S.’s sacred legal system. In fact, it was not until 1880 in Strauder v. West Virginia that it was deemed unconstitutional to exclude Black people from jury selection entirely. Yet even after this decision, racial exclusion continued. In the famous case of Scottsboro Boys in 1931, Samuel Lebowitz, the defense attorney, claimed that the state of Alabama purged Black citizens from the rolls in order to ensure an all-white jury and convictions against the accused Black youths.

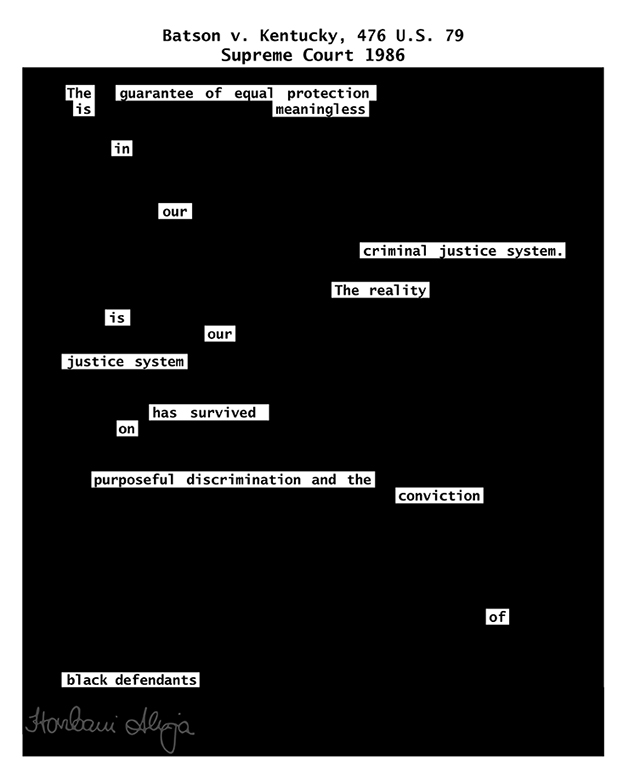

Batson’s objection to the jury composition and the peremptory challenges made its way to the Supreme Court. In Batson v. Kentucky the court ruled that eliminating potential jurors based on race violated both the 6th Amendment’s guarantee of a fair trial and the 14th Amendment’s equal protection under the law. This landmark case was and still is a crucial victory toward achieving a more fair and representative legal system. It enforced the need for neutral reasons to challenge a juror and allowed for fairer trials. It also paved the way for J.E.B. v. Alabama ex rel. T.B. in 1994 which decided that Batson’s ruling extended to gender discrimination as well.

Still, like many progressive Supreme Court decisions, its impact must be contrasted with an aftermath of limitations. First, the decision only applied to a small number of criminal trials. This means that racist jury selection still plays a large role in the justice system. Nearly 20 years after Batson v. Kentucky, the Mississippi Supreme Court had to retroactively remove a murder conviction after the prosecution used 15 challenges to remove Black jurors. Additionally, in a 2010 Equal Justice Initiative study they found, “in Houston County, Alabama, 8 out of 10 African Americans qualified for jury service have been struck by prosecutors from death penalty cases.”

“Batson is a crucial step toward justice but is clearly not enough to stop peremptory challenges from being used to racially discriminate and stack juries.”

Therefore, it is time for new solutions. First, jury pools must become more diverse.

In Hennepin County, Minnesota, “the county has a Black population of 13%, the percentage of Black jurors in 2020 was 6.2%”, but leading defense attorneys are pushing for better data collection to monitor progress, regularly updating jury lists, and ensuring employers are required to pay employees on jury duty.

In conjunction with these basic changes, the Batson ruling must be strengthened at the state level. Fines and steeper punishments must be handed out for repeated racially-biased challenges from lawyers. Finally, there can be no progress without a recognition of the past. This means that the ruling of Batson v. Kentucky must become applicable to cases occurring before the 1986 decision for those still serving sentences or on death row. This retroactive application is a step toward acknowledging the history of racist influence in the legal system and jury selection. While it will not reverse the immense harm for those convicted, it is a step toward progress and a move away from superficial reform.

The legal system supposedly dedicated to fighting inequities must look inward and hold itself accountable: that starts with improving upon Batson v. Kentucky until the right to trial by jury is fair and equitable for all.

David McDaniels is an Intern at ICAAD and is a junior at Georgetown University from Westchester, NY. He is studying Government and Sociology while serving as president of the campus ACLU chapter.