By Chris Mansa LaPorte and Hana Porter

August 3, 2021

Brown v. Board made it illegal to segregate schools based solely on race, but the promise of racial equity in education remains unfulfilled in many parts of the country, including the largest school district in America, New York City public schools.

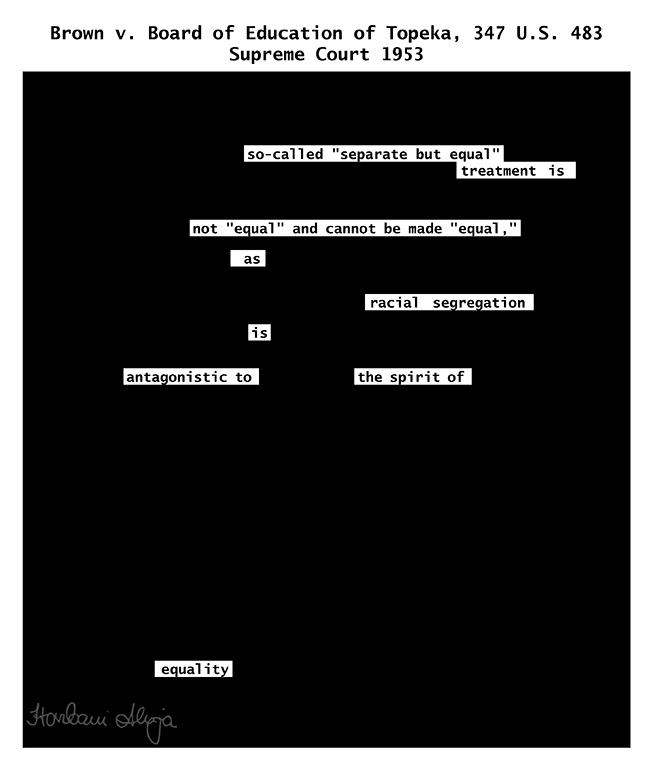

Dicta’s artist in residence, poet and public interest attorney, Harbani Kaur Ahuja writes, “the thin disguise of ‘equal’ accommodations will not mislead anyone, as it is conceived in hostility to, and enacted for the purpose of humiliating, citizens of color” referencing Plessy v. Ferguson which established the principle of “separate but equal.” In her poems, Ahuja highlights, or rather, reveals, the racism entrenched in our justice system that haunts our institutions today.

New York City public schools remain one of these institutions, as well as education in the U.S. more broadly. Black and Latinx students face the consequences of systematic underfunding of low income public schools and poorly executed education policy. We are highlighting the need for accountability in the New York City education system and funding mechanisms through our proposed Social Work Internship Review Board that will collect data on these disparate impacts at the school level and demand that the promises of racial equity are fulfilled.

The Long Fight for Education Equity

There is a legacy to our efforts. Fifty eight years after Plessy, Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP fought and won Brown vs. Board of Education, making it illegal to segregate schools solely based on race, even when the “tangible” factors of the schools may be equal. Their strategy started well before Marshall with a study commissioned by the NAACP in the 1930s that found, without surprise, that facilities serving Black folks were never equal. NAACP leadership created the “equalization strategy,” a series of lawsuits that demanded equal learning conditions for Black students without directly challenging Plessy. The NAACP’s legal advocacy led to the incremental racial integration of schools and other anti-segregation wins related to voting, housing and transportation based on the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which “prohibits states from denying any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the law.” This paved the way for Brown v. Board of Education.

In Ahuja’s Brown v. Board of Education poem, she writes, “so-called ‘separate but equal’ treatment is not ‘equal’ and cannot be made ‘equal’ as racial segregation is antagonistic to the spirit of equality.”

Marshall’s second argument was that the essence of segregated schools made Black students feel inferior and therefore should not be legal. While this was a landmark case in its time, we cannot ignore the persistent challenges to racial equity, particularly in education.

The Shortcomings of Brown in NYC

In our New York City Public School system, Black and Latinx students are more likely to attend schools that are underfunded, under-resourced, and low-performing than their white counterparts. According to the New York City Council, 71.1% Latinx students and 67.8% of Black students attend schools where more than 75% of students experience poverty.

“Racial segregation is antagonistic to the spirit of equality.”

While Brown v. Board ruled that racial segregation in public schools is unconstitutional, today New York City’s public school system remains one of the most segregated educational systems in the country. There have been City attempts at school integration, from bussing to School Choice to De Blasio’s Fair Student Funding (FSF) Plan. These were no doubt hard-fought policy decisions, but when we hear that 74.6% of Black and Latinx students attend schools with less than 10% white students, we have to do better. Institutional racism is pervasive in our society and especially in the policies and practices in our school system. As Beverly Daniel Tatum describes, cultural racism is like smog, “sometimes it is so thick it is visible, other times it is less apparent, but always, day in and day out, we are breathing it in.”

We don’t want to be vague here. Institutional racism can appear in education through policies and practices such as school suspension, gifted programs, and cultural norms that blame poor people for being poor and painting poverty as personal – as opposed to an institutional – problem such as the myth of meritocracy and institutionalized poverty. Statistics consistently reveal that Black students are three times as likely to get suspended from school than white students. Black girls, specifically, are over five times more likely. Overwhelming research indicates that suspensions are purely punitive and likely lead to decreased academic achievement, suspension recidivism, and increased drop out and expulsion rates. Decades of research demonstrate how school disciplinary policies and administrators’ discriminatory patterns only deny Black student’s access to better-resourced schools and psychologically perpetuate harm and trauma.

The myth of meritocracy prevails in gifted education programs that often privilege those whose basic needs are consistently met and ignore those who the system fails at large. Imagine what it’s like for students competing to get into a gifted school. One has to help care for their younger siblings because their parents are working multiple jobs to send money to their grandparents in another country. Another’s family faces housing instability and moves from shelter to shelter. Another attends an under-funded school and is not getting the academic attention needed to support their precocious abilities. All of these students compete with the students who attend the over-funded public schools and have tutors for their entrance exams.

This is not a level playing field. Gaining entrance to a gifted program is far from equal and purely merit-based. School Choice, the lottery system for schools, may have been well-intended, but in practice, it has resulted in severe racial and economic school segregation as many Asian and white families are able to pull their children from underperforming and under-resourced schools and move them into gifted programs. Now add onto these policies, practices and norms, institutionalized poverty.

Institutionalized poverty is another broad subject that we can only briefly touch on here, but its impact is generational. Studies have found that children living in poverty are more likely to experience adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) such as increased exposure to violence, food insecurity, parental incarceration, and a lack of basic needs like health care and safe housing. Poverty and increased exposure to ACEs disproportionately affects Black and Latinx children and creates vulnerability to toxic stress, which is when the body experiences a prolonged stress response to both frequent and intense situations or events. However, often the schools serving these communities do not have the resources to address these needs which impact health, mental health, and consequently, academic achievement.

This brings us back to the promise of Brown v. Board. Not only have Black and Latinx students been funnelled into underfunded schools, but the idea of equality has not delivered racial equity. Policymakers and administrators must recognize the historical and societal factors that shape our student’s lives. Equality is not equity if schools do not support Black and Latinx students with the resources, sound basic education, and academic and social-emotional support they need to thrive in school because of exposure to intergenerational and ongoing trauma perpetuated by racially discriminatory institutions.

“The New York City Department of Education (DOE) is the largest and one of the most segregated school districts in the United States.”

The New York City Department of Education (DOE) is the largest and one of the most segregated school districts in the United States. Funding disproportionately supports gifted education programs and specialized schools, to which Black and Latinx students are often denied access due to institutionalized racism. As demonstrated over the past decade, promises from policy makers to improve access to education for all have been empty. It’s time for us to demand change.

Filling the Funding Gaps

Since the police murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and many other Black lives since June 2020, young activists have been reminded of an important organizing principle: follow the money, always follow the money. One way to do that is to understand the government’s power to hold institutions accountable through funding which is why we must defund the police. We must also recognize how education has been incrementally defunded for years. Education is not only an essential service, but it is also a human right, a human right that has been continuously ignored for Black and Latinx students. Nonprofit organizations and the private sector have been supplementing funding for low-income schools, implementing additional programming and offering donated resources to fill the gaps left by the federal, state, and city education departments. However, nothing can substitute the reach of government.

As mentioned earlier, another lack in the NY State educational program is the Fair Student Funding Formula (FSF), which is the weighted pupil-funding model NYC uses to provide additional funding to students based upon the following criteria: low-income students, English Language Learners, students with disabilities, students needing special education services, and students who are academically advanced. While this formula intended to distribute funds more equitably, it has actually directed significantly more funding to “specialized academic” schools that already have some of the most coveted academic opportunities in the city. In 2017, only 15% of these students were Black or Latinx. In addition, the FSF has never been fully funded until this year.

COVID-19 has also revealed many of the educational inequity gaps, amongst others, in New York City. In response, the DOE is working to make changes for the upcoming school year for 2021-2022. Part of this includes FSF being fully funded for the first time.

The FSF will be used to improve learning conditions and teach socio-emotional skills for the 1.1 million students in NYC public schools. This year’s focus is on emotional and mental health, specifically concerning trauma and anxiety caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. To support this mission, the city is launching a citywide initiative called “Bridge to School” that will focus on creating a safe and supportive learning environment for every student through new partnerships. The DOE is also hiring 500 new social workers and other mental health support staff so that schools have at least one social worker or school-based mental health clinic. With the DOE’s invigorated interest in mental health and finally adequate funding, this is an opportunity for schools of social work to get in the game and advocate for the communities they work with on a structural level. Our proposed Social Work Internship Review Board will help ensure programs are sustainable and continue to advance racial equity, as promised.

Social Workers Making Change

Black and Latinx students are not receiving an equitable education due to generations of systemic racism ingrained in the United State’s institutions- education, health care, real estate, and criminal justice. Because systems such as these practice and perpetuate racism, discrimination, and implicit/explicit bias against Black and Latinx students and their families we are calling for collaboration with New York City Department of Education, Principals and administration, and schools of social work in New York to develop the Social Work Internship Review Board (SWIRB) that can support the assessment of public school funding based on a holistic perspective of mental health by 2023.

With the implementation of a Social Work Internship Review Board in every public school that has a Social Work intern, each intern will be able to help identify the funding deficits in the schools. Through critical assessments and evaluations with the school, students, and guardians, the interns can identify and document critical mental health deficits like clean drinking water, after-school programming, additional Social Workers, and barriers to food security, and assist the schools in requesting adequate funds to address these needs. School social work internships are already fantastic opportunities for both the public schools and the interns, but it’s time for us all to do more to ensure Black and Latinx students receive the equitable education promised in Brown v. Board.

Chris Mansa LaPorte was born in France, Ayitian-American raised in Connecticut. He is a recent graduate with a masters in social work from Columbia University. His focus is providing equitable resources and mental health/social emotional well-being for our youths, for a better future and sound basic education. Contact Chris on LinkedIn or email him here.

Hana Porter was born in Wuhan, China and raised in New York City. She is also an MSW graduate from Columbia School of Social Work where she focused on school-based and school-linked services and international social welfare. Email her here.

Both students took ICAAD’s 2020 course at Columbia University, Disrupting Unjust Systems Through Behavioral Science & Design Thinking.