By using data, technology, and the law to combat violence against women and girls, our programs improve transparency, consistency, and accountability within justice systems.

Background

Gender-based violence (GBV) is an epidemic that affects over a third of women worldwide. Prevalence studies conducted in Pacific Island Countries (PICs), using the World Health Organization methodology, show much higher prevalence rates of GBV with 60%-80% of women and girls who have faced intimate or non-intimate partner violence in their lifetime. The violence women and girls face is shaped broadly by gender bias and stereotypes, specific customary practices, and myths, which penetrate all aspects of social, economic, cultural, and political life. One important example is access to the formal justice system. There are often numerous barriers to accessing the justice system and even if they are able to get their cases before the court, perpetrators often times receive disproportionately low sentences or no prison sentence at all for domestic violence and sexual offenses.

To more fully understand the context of GBV in PICs, ICAAD conducted strategic assessments on 12 Pacific Island Countries. These assessments looked at the prevalence of gender inequity with various systems: Judicial, Legislative, Health, and Law Enforcement, and how specific customary practices shaped those systems. These assessments helped ICAAD target gender-bias in judicial decision making as a focus of its efforts in the region.

Example of gender-bias in the courts affecting access to justice:

Facts: A pregnant woman was killed by her husband. Prosecutors dropped the charges of killing an unborn child and had reduced the murder charge to manslaughter for the death of the wife, which was a significant reduction in the possible sentence the perpetrator could have received.

Judicial Reasoning: The judge selected a lower sentence range for the perpetrator for the following reasons:

1. The victim provoked the Defendant to violence by talking about past infidelity that was already known to the Defendant

2. The victim further provoked the Defendant because she bit down on his fingers when he was choking her; and

3. The victim’s family engaged in a customary reconciliation ceremony where a cow, two pigs, fish, women mats, and the equivalent of $780 USD.

Due to the charge of murder being reduced to manslaughter in this case, the range of the penalty was lowered to 10 years from life in prison. Moreover, instead of focusing on the vicious acts of the perpetrator, the judge engaged in victim-blaming, stating that there was a “substantial degree of provocation.” There was no mention of self-defense. The judge further reduced the sentence because the family of the victim received compensation through cultural reconciliation. The final sentence given was 5 1/2 years.

Testing Assumptions

Through the assessments conducted with our partners, we found a number of gaps, particularly in how courts were handling domestic violence and sexual offence cases. The assessments revealed that judges in the Pacific were giving undo weight to gender-stereotypes and the cultural practice of reconciliation in order to remove or lessen accountability of the perpetrator.

One of the main assumptions we wanted to test was whether we could quantitatively unearth a pattern and practice of discrimination from domestic violence and sexual offence cases. In 2014, We started with a very small mini-pilot of analyzing 60 cases in Fiji to see how judges were treating perpetrators who had committed GBV. In our analysis, we found that judges were impermissibly reducing the sentence of perpetrators, and sometimes, fully or partially suspending the sentence if customary reconciliation had taken place. This occurred in over 50% of the cases reviewed.

Designing Approach

After uncovering significant levels of bias in GBV cases through a mini-pilot, we wanted to design an approach that strengthened judicial accountability. In 2014, we met with 30 stakeholders, including civil society, UN agencies, and government in Fiji. Through those consultations we broadened the case law analysis on customary practices to include looking at the role of gender stereotypes and rape myths. Additionally, we decided to look to if the patterns of bias were similar in other PICs.

We then developed a methodology that looked at 25 key variables in each case, and conducted analysis covering 7 countries and approximately 1,000 GBV cases.

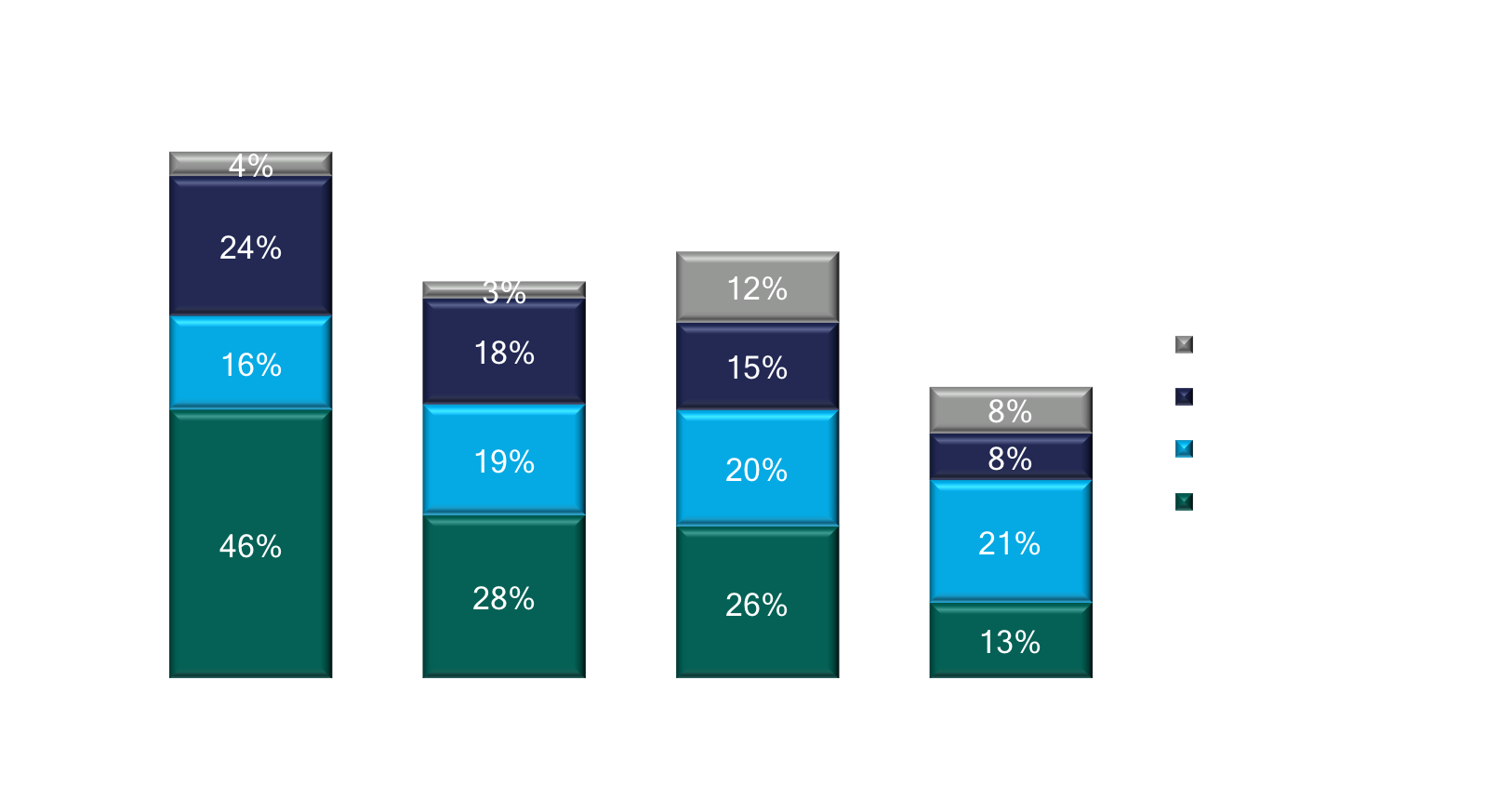

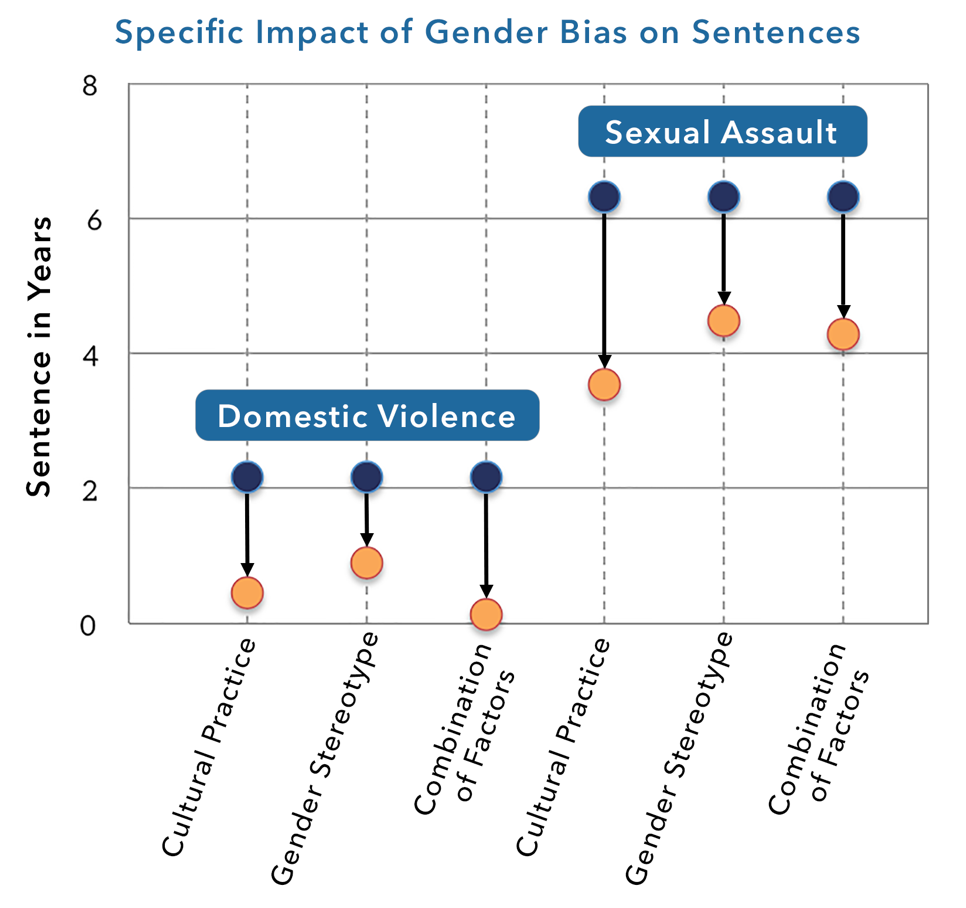

This chart breaks down the overall impact of sentence reduction in sexual assault (SA) and domestic violence (DV) cases. The blue dots represent the starting sentence including all aggravating factors the judge considered. All mitigating factors (permissible and impermissible) were then subtracted to arrive at the final custodial sentence. The average reduction in sentence for DV cases was 59%, and for SA cases was 40%. It was found that the judge simply used his/ her discretion to partially or fully suspended the sentence in 52% of DV cases and 15% of SA cases.

Intervention

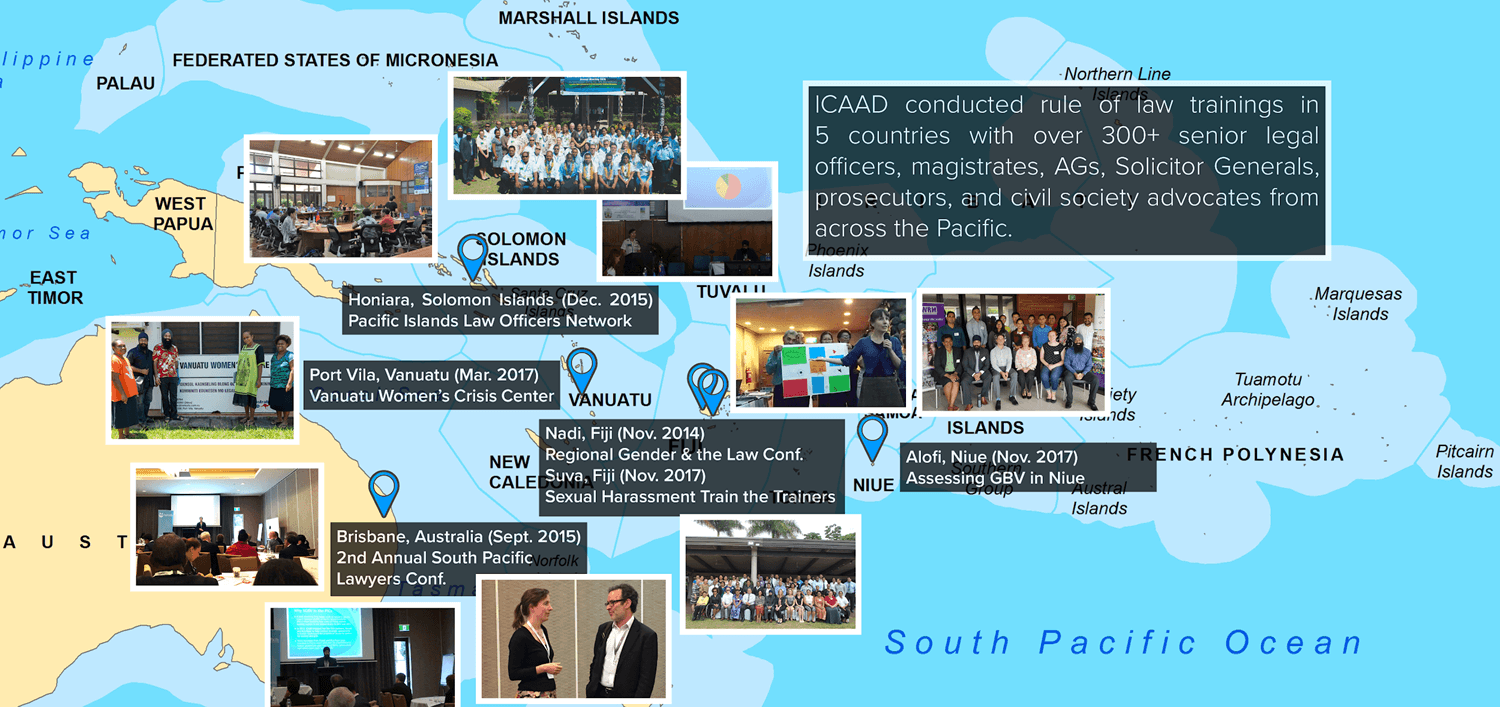

Outside of the trainings for Attorney Generals, prosecutors, magistrates, and CSOs highlighted in the map above, implementation included:

- Publishing An Analysis of Judicial Sentencing Practices in Sexual & Gender-Based Violence (SGBV) Cases in the Pacific Island Region with our law firm partner DLA Piper

- Building the TrackGBV Database with our technology partner Conduent, which houses 20 years of analyzed GBV case law from 12 countries

- Judicial and legislative change (Fijian Directives in 2018, Amendment to sexual offence legislation in Solomon Islands in 2016) change

- Publishing Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in the Pacific Islands: Handbook on Judicial Sentencing Practices with law firm partner Clifford Chance in 2018

Impact

Systems change takes time and measuring true impact takes several years if not decades. To date, we can measure our impact in the region from the following:

1) Adoption of a jointly drafted Directive by the Fijian Judiciary in 2018

At the end of 2017, we met with the Chief Justice and Chief Magistrate for Fiji to request that we jointly draft Directives based on the TrackGBV analysis. Directives are orders that the Chief Justice usually issues to ensure that decisions issued by judges comply with the law and are consistent. The Directives that we drafted with the judiciary were issued to all the magistrate judges in Fiji on May 2018. When looking at case law from that period, judges are echoing the rationale of the Directive on important points regarding reconciliation and first time offender status.

L to R: Jaspreet Singh (ICAAD), Scot Fishman (Manatt), Chief Magistrate Usaia Ratuvili (Fijian Judiciary), Hansdeep Singh (ICAAD)

2) Amendment to Sexual Offence Legislation in the Solomon Islands in 2016

After ICAAD’s training in the Solomon Islands in 2015, which was geared towards Attorney Generals and the Department of Public Prosecution, the Penal Code on Sexual Offences was amended by the Solomon Islands (2016). During the training we spoke with the Attorney General of Solomon Islands who said our data would help move legislation that had been stuck in Parliament for over two years.

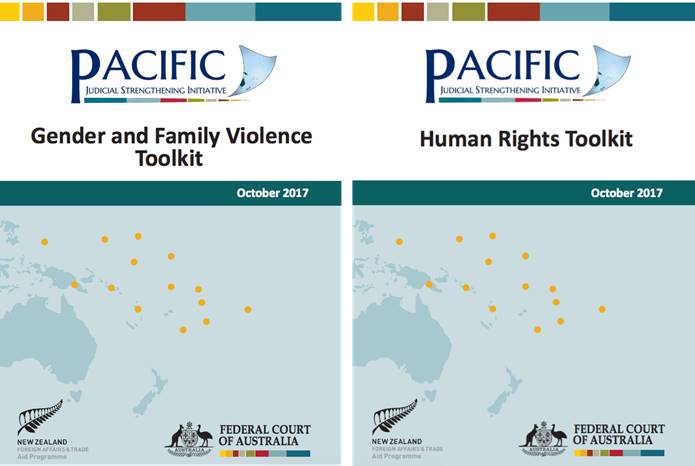

3) Integration of ICAAD’s TrackGBV Findings into Tool-kits for the Legal Profession

The Pacific Judicial Strengthening Initiative (PJSI), an initiative of Federal Courts of Australia, integrated our findings into both their Family Violence and Human Rights Toolkit. PJSI trains Chief Justices throughout the Pacific region.

For ICAAD, sustainable change comes from having our methodologies and data integrated into local CSOs and government trainings and policies. Therefore, we distribute our data and reports to local stakeholders, including presenting at conferences that bring together key stakeholders from 17+ PICs. We continue to conduct trainings as requested.

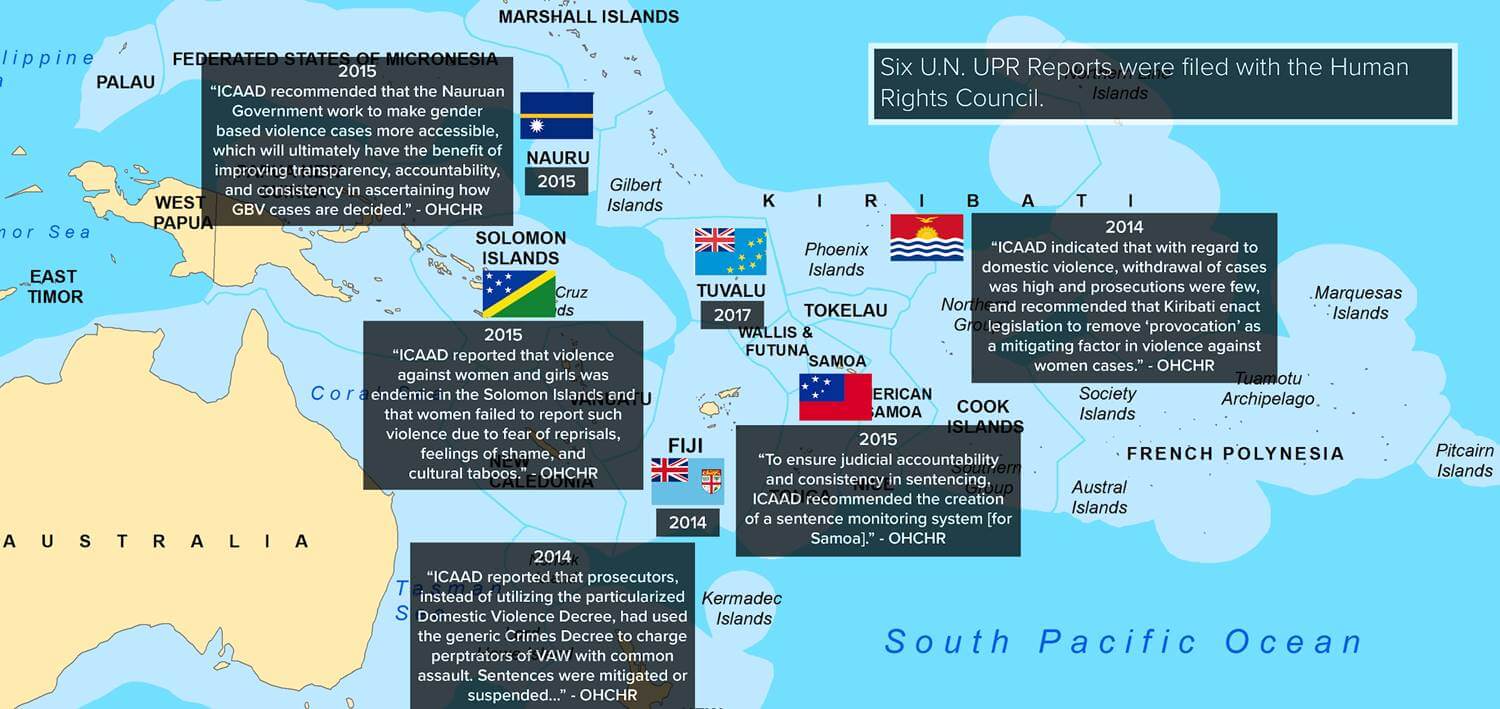

ICAAD also engages in international human rights advocacy on behalf of local partners. Our reports have been cited by various United Nations (UN)treaty body committees and the Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights.

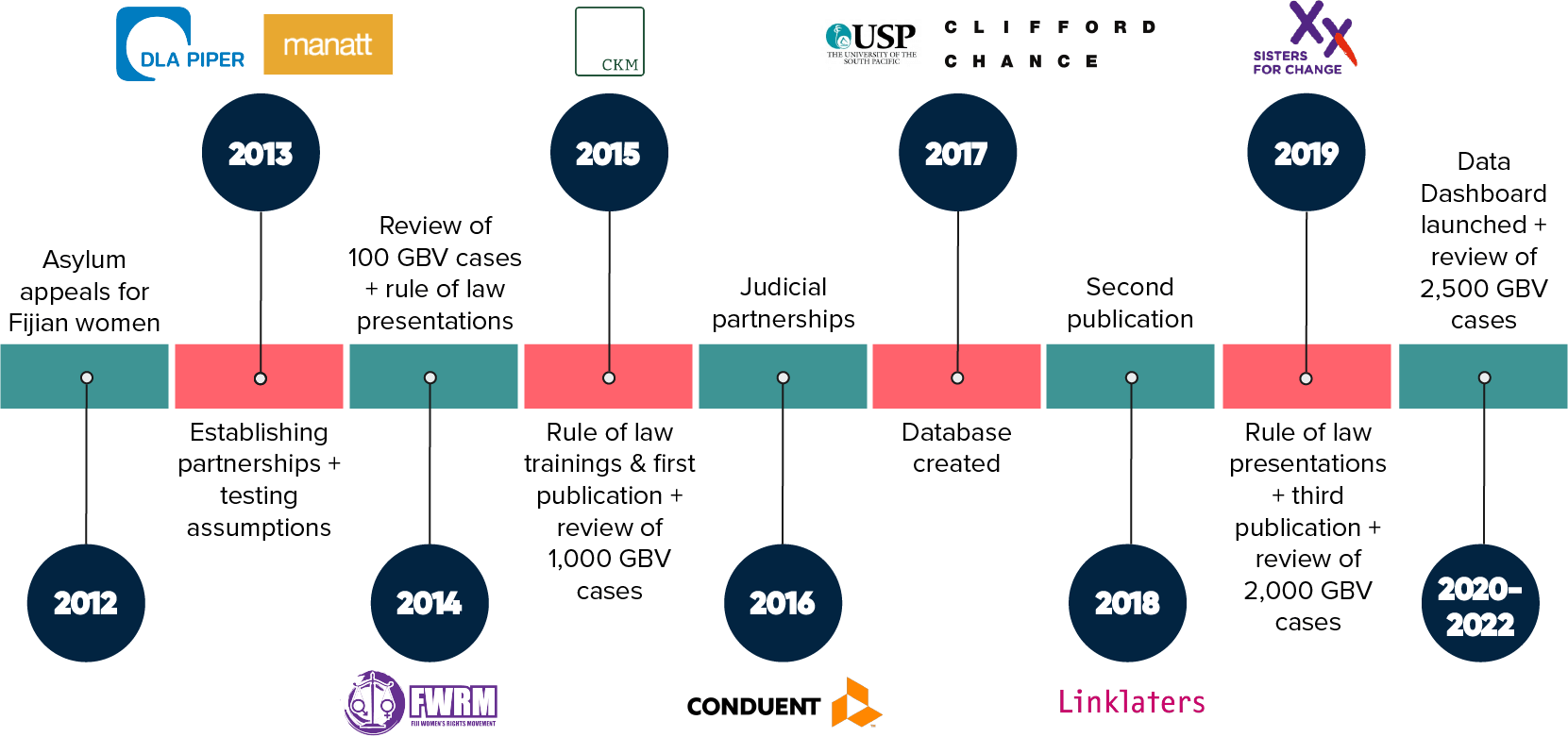

Timeline of Development