TOOLKIT

Mining and Community Power in the Solomon Islands

Know your rights, use your power, protect your future

The extractives industry including logging and mining have been causing harm to communities and the environment for decades in the Solomon Islands. This toolkit was designed to support landowners, community leaders, conservation groups, and individuals who care about their communities and the environment to rebuild their power to make decisions in the best interests of present and future generations.

As mining companies move in to replace logging, the risks to land, culture, and future generations continue. We believe that the people most affected should be the ones leading the response. This resource brings together strategies, legal knowledge, and community organising tools shaped by our shared experience and commitment to Indigenous self-determination, environmental justice, and climate action.

Who we are and why we’re doing this?

This project is a collaboration between ICAAD, the Development Services Exchange (DSE), Apunepara Ha’amwa’ora Natural Resources Association (AHRNA), and a CBO from Lauru/ Choiseul Province, supported by funding from the Earth Rising Foundation.

This toolkit empowers communities across the Solomon Islands to influence decision makers about mining and protect what matters most to them. When we say community, we mean everyone who cares about the future of their place: village leaders, people in churches and community groups, members of civil society organisations and NGOs, and anyone who wants a say in decisions that affect their land, water, and way of life. Whether you have formal power in an institution or you’re speaking up from your village, this toolkit is for you.

Communities have real power when they understand how decisions get made, know their rights, and work together. This toolkit helps you ask the right questions, understand the laws, and organise effectively so your voice matters in decisions about your future. You have the power to shape what happens in your community. This toolkit shows you how to use it.

How to use this toolkit

This toolkit is designed to be practical, easy to understand, and useful whether you’re new to these topics or have been resisting harmful activities by the extractives industry for years. You don’t need to read it all at once. Each section works on its own, so you can go to the parts that are most relevant to you or your group.

Some of these tools will work best in groups, like a tribe, indigenous community, landowners, community association, conservation group, or churches. Others you can use this toolkit on your own to better understand the system and your options.

This toolkit was designed for you. Please take what’s useful, share what you learn, and add your own wisdom as you go.

In this Toolkit

- Setting the Scene

- The Bigger Picture

- How can things change?

- What do the laws say?

- Who has the power to make decisions?

- Recent Policy Developments

- Building Power

- Points of Intervention

- Advocacy Pathways

- Tactics

- Understanding the Risks

Setting the Scene

Logging and mining have shaped how land is used in the Solomon Islands for decades. Large-scale logging has led to widespread deforestation. This damages water systems and reefs, and disrupts how communities make a living. When companies cut down forests, they destroy the ecosystems that support wildlife and keep water clean. Soil washes into rivers, streams, and coastal areas. This damages the coral reefs and mangroves that people depend on for fishing.

As forests are running out, many companies are turning to mining, especially for gold and bauxite. Mining brings new problems to land, rivers, and communities. It changes how rivers flow and contaminates the streams and watersheds where people collect drinking water. Mining increases soil erosion. Sacred sites and cultural heritage places often get destroyed. Communities lose access to their subsistence gardens where they grow food for their families.

What happens locally connects to bigger global problems. Logging and mining release carbon into the atmosphere by clearing forests and disturbing ecosystems. They also remove natural defences like mangroves. These help protect against floods, erosion, and storm surges. All of this adds to global climate change and local risk.

In the Solomon Islands, climate change is already happening. Sea levels are rising. Cyclones are getting stronger. Weather patterns are shifting in ways that affect farming, fishing, and daily life. Decisions about allowing extractive projects are complex. This toolkit helps communities understand the impacts, weigh their options, and advocate for future generations.

Voices of Traditional Landowners

In developing this Toolkit, the Development Services Exchange (DSE) conducted a survey with traditional landowners in Guadalcanal, Isabel, and Malaita provinces. The survey gathered perspectives on logging and mining activities. The preliminary findings revealed widespread feelings of exclusion, lack of consultation, and a dissatisfaction with current practices. Key preliminary findings include:

- People found out about extractives industry operations informally, such as observing machinery or hearing rumours, as opposed to formal notification which is required by law.

- Where consultation occurred, it was often late, superficial, and limited to select individuals.

- While some people mentioned short-term economic benefits like local employment or road access, the majority reported disruptions to local livelihoods and not enough compensation.

- Extractive companies often made existing divisions and conflicts worse or created new disputes, especially when companies favoured certain families or leaders over others.

- People have been frustrated by the lack of enforcement of community and environmental protections, opaque agreements, and the neglect of traditional governance systems in the process.

- People highlighted the devastating environmental impacts including deforestation, river pollution, and loss of biodiversity and noted that companies rarely made an effort to rehabilitate affected areas or monitor environmental impacts.

The full analysis will be available from DSE.

The Bigger Picture

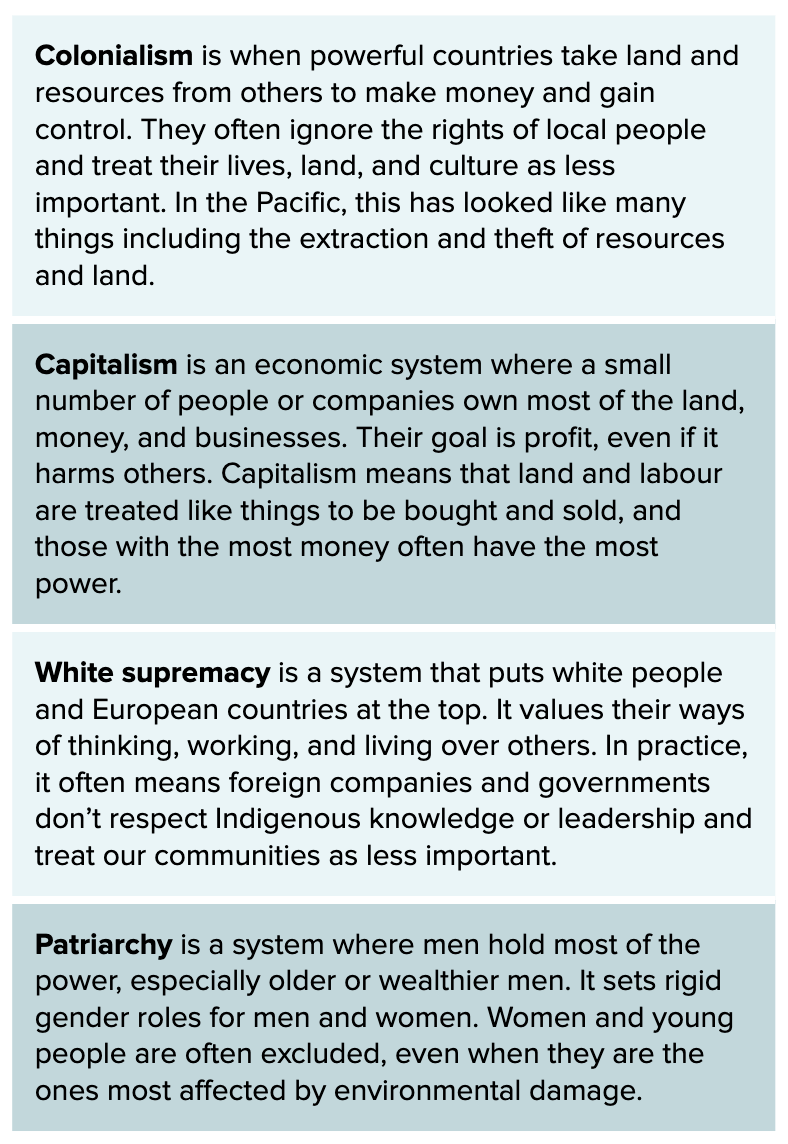

When we talk about the harms of mining, we usually talk about what we can see: polluted rivers, damaged farms, broken promises, and conflict in and among communities. When we look deeper, we can see how the extractives industry is connected to larger systems. These systems are shaped by long histories of who holds power and who doesn’t. We might call these systems that harm communities, systems of oppression.

What do we mean by “systems of oppression”?

A system is like a net. It’s made up of different parts like ropes, knots, and weights, and together it does something, like catch fish. Some systems help us thrive, like kinship systems that keep us connected. On the other hand, some systems are set up in ways that keep certain people in power while taking advantage of others. Those are systems of oppression.

Systems of oppression help us see more than an inadequate law or unaccountable leader. They’re bigger than that. Systems of oppression shape which laws get written, who is listened to, what kind of development is valued, who carries the risk, and who gets left behind. When we look at the extractives industry, there are four main systems of oppression at play.

These systems don’t work alone. They reinforce each other, especially when it comes to the extractives industry.

How Systems of Oppression Work in Practice

You may be familiar with what happened in Bougainville. In the 1970s, a massive copper and gold mine called Panguna was opened by Bougainville Copper Limited, majority-owned by a foreign company (Rio Tinto), with support from the Papua New Guinea government.

Local landowners were not properly consulted. Their land was taken, forests were cleared, and their rivers were poisoned by waste from the mine over time. The company made billions of dollars, and locals got very little. Even most jobs in the mine were given to outsiders. When people protested, they were ignored.

Women in particular raised early concerns about the destruction of sacred sites and the impact on their water sources, but their voices weren’t taken seriously. When young men started resisting, the government sent in police and military forces. Things escalated into a war.

From 1988 to 1998, the conflict around Panguna turned into a full-scale civil war. It’s estimated that up to 20,000 people died, and thousands more were displaced. The mine has shut down, but the trauma and division remain.

Bougainville shows us that the struggles we face here in the Solomon Islands are part of a much bigger pattern. Around the world, we see what happens when powerful companies are given space to operate without real checks. Land is taken. Promises are made, then broken. Development moves forward, but the benefits often don’t reach the communities who ultimately pay the price. Voices, especially those of women and elders, are pushed to the side. In Bougainville, the pressure built over time until it broke. It wasn’t just one company or one decision. It was a system that made it easy to ignore the people most affected.

Photo credit: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Why Community Approval Matters

The Bougainville conflict shows what happens when companies and governments treat legal permits as the only permission they need. There’s another kind of permission that’s just as important: social licence.

| Social licence exists when a community genuinely supports and accepts a project. It goes beyond meeting legal requirements, it is built on trust, mutual respect, and ongoing dialogue. Without this trust and consent, projects risk community resistance, delays, and conflict that can threaten their success. |

Traditional landowners have voiced that companies often claim they have community support when they really don’t. They point to meetings with a few selected leaders, middle people, or payments to certain families as proof of approval. Real social licence means the whole community understands what’s happening and genuinely agrees to it.

This principle is recognised internationally as Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) which is the right of Indigenous peoples to say yes or no to projects affecting their land and resources. FPIC comes from decades of Indigenous struggles worldwide and is now part of international law, but Solomon Islands domestic law still doesn’t protect this right.

| Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) is a process of giving or withholding permission. It is the right to say yes or no to developments without coercion and with enough time and information. |

Preliminary findings from DSE’s research with landowners across three provinces show that most extractives projects in the Solomon Islands lack social licence. Communities feel bypassed, inadequately consulted, and excluded from decisions about their own land.

What This Means for Us

These patterns from Bougainville and the experiences documented in our own communities show us that mining is expanding across the Solomon Islands under the same problematic systems. Companies are granted licences and arrive with promises: jobs, roads, development. In communities under pressure, these offers can be hard to refuse.

When decisions are made without meaningful consultation or accountability to the people most affected, the consequences can be severe. Land can be permanently lost, rivers and gardens damaged, and communities fractured. Too often, the people who feel the impacts most, such as women, young people, and those with long-standing ties to the land, are not the ones making the decisions.

Still, this is only part of the story. Across the Solomon Islands and the wider region, many communities have come together, raised difficult questions, and found ways to safeguard what matters most is their land, water, and culture. Throughout this Toolkit, you’ll find stories of these successes and valuable lessons learned. They demonstrate what can be achieved when people are informed, organised, and united.

Every community will face different choices. Knowing these patterns, and learning from those who’ve come before us, helps us prepare for the road ahead.

How can things change?

If you’ve ever wondered why we see the same patterns, even when the harm is obvious and people speak up, you’re not alone. Knowing something is wrong is one thing. Changing it is another.

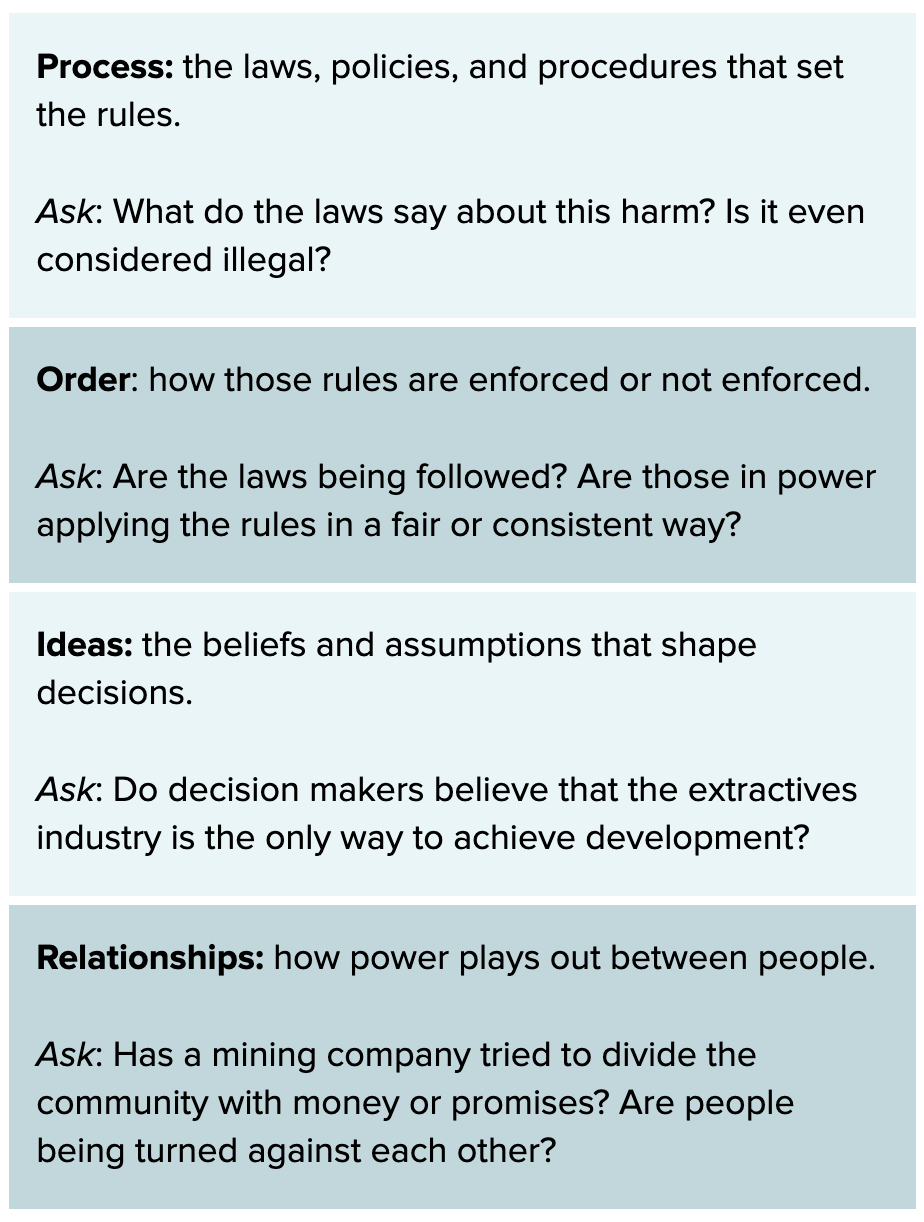

To build a strong strategy for change, we need to understand how these systems work in practice. It’s typically not just about one bad actor. The harm caused by the extractives industry is made possible by systems of oppression that organise, maintain, and justify power.

We can call the tools they use to do so: technologies of power. These are the ways that power is organised, maintained, and justified. Some of these are written into law. Others show up in day-to-day interactions or beliefs that seem normal but actually reinforce inequality.

There are four main technologies of power to pay attention to. This helps us identify where to take action. For example, are we concerned with the law itself, how it’s being enforced, the beliefs that may be shaping that interpretation, and/ or individual conflicts between peoples that may be reinforcing systems of oppression?

In the next section, we’ll look at process and order and look at the specific policies and laws shaping the extractives industry in the Solomon Islands and explore how they connect to this bigger picture.

Case Study: Wagina

Sometimes the problem is not that laws do not exist to protect communities. The problem is that those laws are not being enforced properly. The Wagina Island case shows the difference between having legal protections on paper and making sure they actually work in practice. It demonstrates how communities can use existing laws to demand proper consultation and environmental protection.

Their Situation

Solomon Bauxite Limited wanted to mine bauxite on Wagina Island, but the process was deeply flawed from the start. In 2019, a government committee cancelled the mining permit because the company had not shared enough information and local people were not properly consulted. Only one meeting was held back in 2013, and most villagers were not there. When new information came later, it was not shared properly with the community. The case then went to the Minister of Environment for a final decision. Local communities faced the possibility of a mine that could damage their fishing areas, seaweed farms, gardens, and wood collection areas, all without proper consultation or their informed consent.

What They Did and Why

The Wagina Island communities focused on demanding that existing laws be followed properly rather than accepting a flawed process. They highlighted the lack of proper consultation. Communities pointed out that meaningful consultation had never happened, with only one inadequate meeting in 2013 that most villagers missed. They used this to show that legal requirements for community involvement were not being met.

They demanded transparency about environmental impacts. When the company failed to share enough information about how mining would affect their land and sea, communities called this out as a violation of their right to make informed decisions about their land.

They called for direct ministerial engagement. Rather than accepting decisions made by officials who had never visited the island, communities specifically requested that the Minister of Environment come to Wagina and speak directly with the people who would be affected.

They asserted their land rights under existing law. Communities made clear that any big project had to be done with their knowledge, agreement, and participation, pointing to legal frameworks that were supposed to protect these rights.

They gained support from human rights organisations. Groups like Amnesty International backed their calls for proper consultation, adding pressure on the government to follow its own procedures correctly.

|

Key Lessons

The Wagina Island case demonstrates that when communities understand their legal rights and can clearly show that proper procedures are not being followed, they can force authorities to slow down flawed processes and demand better consultation, even when powerful mining interests are involved. |

Jenny Schott, CC BY 2.0, via flickr.

What do the laws say?

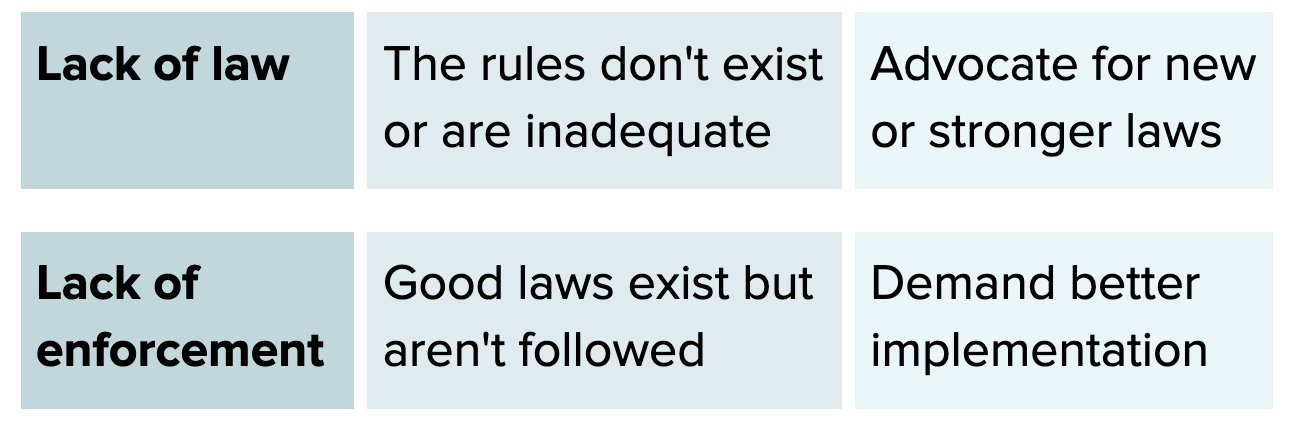

Knowing the law helps us decide whether we need to change the rules or advocate for existing laws to be enforced. This section looks at the legal framework governing mining in the Solomon Islands. We’ll examine who has decision-making power, what the laws require, and where communities can intervene in the process.

In the Solomon Islands, sources of law include:

- The Constitution (1978)

- Acts of Parliament (like the Mines and Minerals Act)

- Regulations made under those Acts

- Customary law (though this can be pushed aside)

- International treaties (though these don’t automatically apply)

After we understand the existing law on an issue, we can decide if the challenge at hand is a matter of a gap in the law or a lack of enforcement of existing law.

Key Laws and What They Actually Say

Parliament is the legislative authority in Solomon Islands which means it is responsible for enacting laws called “acts of Parliament”. Parliament also has the authority to make changes to the Constitution and acts of Parliament. Acts of Parliament include the Mining Act, Environmental Act, and the Lands and Titles Act.

Constitution of Solomon Islands 1978

The Constitution is the highest law in the country and promises to protect the fundamental rights of all Solomon Islanders. It uses language that sounds like it gives Indigenous people control over their land and resources, saying that power belongs to “the people” and that natural resources are “vested in the people and the government.”

However, there’s a gap between what the Constitution promises and what it actually allows. While it says power belongs to the people, it then says this power is “exercised on their behalf by the state.” This means the government is empowered to make decisions for you.

The Constitution does protect people’s rights to their homes and property, but it includes important exceptions. The state is allowed to take someone’s home and property if it’s for “the development and utilisation of mineral resources” or to “promote the public benefit.” Often, the government has decided that mining projects qualify under this threshold.

The Constitution also recognises customary law and traditional practices, but only when they don’t conflict with written laws passed by Parliament. This means that if your traditional laws say the whole community must agree before land can be used for mining, but Parliament passes a law saying only consultation is required, the Parliament’s law overrides.

|

What the Constitution says:

|

Mines and Minerals Act [Cap 42]

This is the primary law governing how mining is conducted in the Solomon Islands. Echoing the Constitution, the law states that all minerals are “vested in the people and the Government of Solomon Islands.” However, it also says the Government has “exclusive right to deal with and develop” mineral resources in the “national interest.”

This means that even if landowners say no to mining, the government is still legally allowed to “compulsorily acquire” or force you to sell your land for mining purposes under the Land and Titles Act. Unlike the law governing logging which involved customary law and landowner consent, the laws related to resources under the ground are under the authority of the central government.

This is a remnant of colonialism and is a common distinction in mining laws in countries that have kept colonial era legislation, even in the Solomon Islands where the majority of land is under customary tenure. Having national authority over subsurface resources makes mineral extraction easier and more profitable for foreign companies.

The law also defines how royalty payments are divided. Mining companies pay 3% royalties, and it is split among the Solomon Islands Government (50%), landowners (40%), and the provincial government (10%). Even though communities bear the direct environmental and social costs, they get a smaller share than the national government.

|

What the Mines and Minerals Act says:

|

Environmental Act 1998

This law requires that all mining projects get environmental approval before they can begin. It makes it a criminal offence to conduct mining without development consent from the Director of Environment. Companies must produce an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and hold public hearings where communities can raise concerns.

However, the appeals process heavily favours those with money and legal expertise. If you disagree with an environmental approval, you must first appeal to the Environment Advisory Committee within 30 days, then to the Minister within another 30 days, and finally to the courts through judicial review.

The strict time limits and need for legal representation make it very difficult for rural communities to use this process effectively. Most communities can’t afford lawyers or don’t even know about the 30-day deadlines until it’s too late. Companies, on the other hand, have teams of lawyers and resources to navigate the system.

This creates a situation where environmental protections exist on paper, but are hard for affected communities to access in practice. The law assumes communities have the same resources as mining companies, which is clearly not the case.

|

What the Environmental Act says:

|

Land and Titles Act [Cap 133]

This law officially recognises customary land ownership by Indigenous Solomon Islanders and places restrictions on selling customary land to foreigners. At first glance, this seems to protect customary land rights.

However, the law contains a major loophole: it allows the state to seize customary land in the “interest of public good” as long as compensation is paid. The government decides what counts as “public good,” and mining projects often qualify under this definition.

If customary landowners want to challenge the government taking their land, they must go through an expensive and complicated court process. This requires substantial financial resources for legal fees, travel to court, and expert witnesses.

This creates an unequal playing field where customary land rights are recognised in theory but can be easily overridden in practice. The law pretends to protect Indigenous land ownership while creating legal pathways for the state to take that land when it benefits mining companies.

|

What the Land and Titles Act says:

|

Process: Revisiting the Mines and Minerals Act

The Mines and Minerals Act creates a three stage process for companies wishing to mine: reconnaissance, prospecting, and mining. With the existing law, there are opportunities in each of these stages for communities to engage in the process: reconnaissance, prospecting, and mining.

|

Reconnaissance involves basic surveys to identify potential mineral deposits. Reconnaissance can be permitted for up to 2 years. Companies must inform landowners, but they don’t technically need consent.

|

|

Prospecting involves more detailed exploration including drilling and sampling. Prospecting can be permitted up to 3 years and extended. In this stage, companies must negotiate “surface access agreements” with landowners. Communities can refuse and/ or negotiate surface access, demand fair compensation, and require environmental monitoring.

|

|

Mining means full scale extractive operations. Mining permits can be granted for up to 25 years. They require environmental impact assessments and public hearings. Communities can challenge the environmental impact assessment process and appeal environmental approval. |

Case Study: Marasa

When mining companies break the law, communities need more than anger to stop them. They need people who understand how the system works and can use legal tools strategically. The Marasa case shows how communities with the right knowledge and solidarity can take on illegal logging operations and win by holding authorities accountable to their own rules.

Their Situation

Logging company Gallego was granted a licence in 2015 but immediately began breaking multiple laws. They skipped required local consultations, environmental impact reports, and site inspections. They expanded operations beyond their licenced area and violated rules about operating close to tributaries. When communities complained about damage, the company offered only one affected village an empty water tank as compensation.

Government officials refused to meet with community members seeking information about the company’s activities. The community faced illegal logging that was causing real damage but had no clear way to challenge a company.

What They Did and Why

The Marasa community, led by Philip Manakako who had experience with anti-corruption work and Solomon Islands bureaucracy, developed a strategic campaign to stop Gallego’s harmful operations.

They used knowledge of the system to access information. When government officials refused meetings, community representatives went to the Forestry Ministry and refused to leave until they were given the documents they needed. Understanding how bureaucracy works helped them know which papers to demand and how to pressure officials to follow procedures.

They built solidarity among people with different viewpoints. The approach involved patient meetings with elders and young people who had different reasons for either supporting or opposing Gallego’s activities.

They created a systematic documentation network. The community built an information network to document damage, track company activities, and monitor shipments. This evidence became crucial for legal challenges and showed how the company was breaking the law.

They pursued formal legal channels strategically. Community representatives lodged appeals and applied for stop notices through proper legal processes. Even though travel by boat was costly and time consuming, they strategised that these legal channels would be the most effective for forcing government action.

They resisted company pressure and stayed focused. Despite receiving financial offers to stop their work, the community continued documenting violations and meeting with company and government leaders, showing their commitment could not be bought.

|

Key Lessons

The Marasa victory shows that when communities have people who understand the legal system and can build unified support, even illegal mining operations backed by government licences can be stopped through strategic use of existing laws and procedures. |

Dan Hetherington, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Who has the power to make decisions?

When we talk about granting permits and approving environmental impact assessments, it is important to be clear about who is making decisions. Institutions don’t make decisions, people do. The “Solomon Islands Government” doesn’t approve mining licences. The Minister of Mines does. The “Mining Board” doesn’t decide whether to fast-track projects. A small group of individuals sitting around a table do.

You might recall that the Constitution empowers the government to make decisions on behalf of the people. This is because they are voted in to represent the people’s interests. They are paid with your taxes, and they are accountable to the people and the public interest.

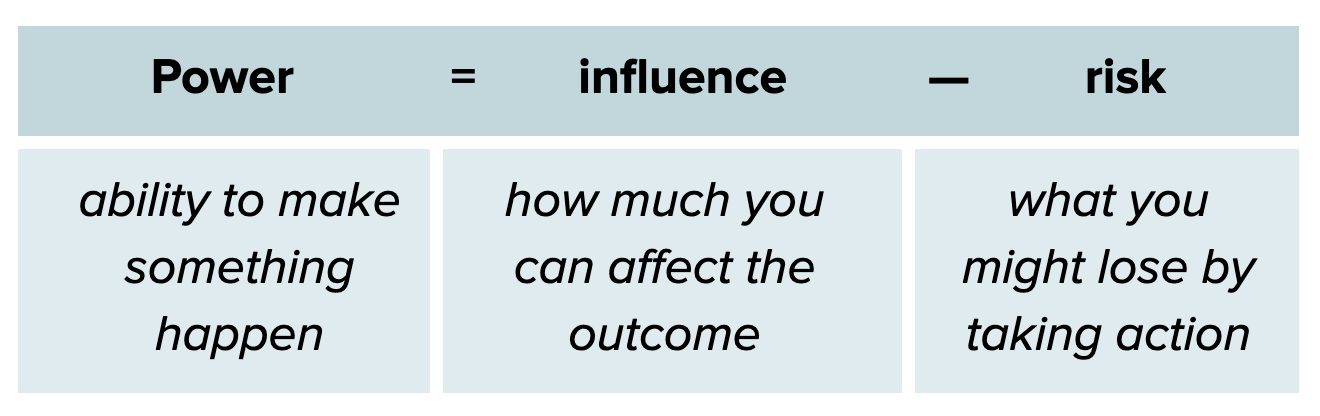

Power is really the ability to make something happen. However, it’s helpful to think about power as our influence over making something happen minus the risk of using that influence.

Knowing can help us increase our influence and reduce our risk. Power isn’t fixed. We can build influence and reduce risk by organising with others. When communities come together, individual people become harder to ignore or intimidate.

With that increased influence, you can make your voices heard on important decisions by the individuals who currently have the power to make the call. In the next section, we’ll look at exactly who has been given the power to make mining decisions and how you can hold them accountable.

Key Decision Makers

Mining Companies apply for permits and conduct operations. They choose where to explore, how much to invest, and negotiate directly with landowners. Companies must follow permit conditions and pay royalties, but they also lobby government and control information about their operations.

Investors and Shareholders are the people and institutions that fund mining companies. These include banks, investment firms, and individuals, often based overseas. They pressure companies for profits and can withdraw funding if projects become too controversial or unprofitable.

Communities have multiple pressure points. When government lobbying isn’t working, campaigns targeting company investors in their home countries can influence decisions. Investors care about reputation and profits, and public campaigns that threaten either can change company behaviour.

In many cases, the decision maker that cares the most about social licence is investors. If investors are alerted to the lack of social licence, they can withdraw their funding from a mining project.

In the Solomon Islands, the Minister of Mines has the final authority on all major mining decisions. The Minister receives advice from the Mining Board but makes the final decisions on permits and licences.

The Minister is the key person communities need to engage with on mining issues, but the Minister must also follow legal processes that include landowner consultation for surface access.

What can the Minister do? |

|

Grant mining permissions

|

|

Allow access to land

|

|

Monitor and enforce

|

|

Set financial terms

|

Photo by Lisa Osifelo at Gold Ridge Mine, Guadalcanal

Recent Policy Developments

National Minerals Policy (2017-2021) – Expired

This is the latest national mineral policy. There was no mineral policy created after this one expired. The Policy was intended to address a number of the negative outcomes resulting from the gaps in the mining laws and regulations. It sought to deliver results that will benefit all three core stakeholder groups, namely the government; landowners, communities and project impacted persons; and mining companies.

Companies will also not lead landowner identification, have standardised land access agreements, enjoy an even playing field by facing greater scrutiny to encourage reputable operators.

While this policy was a response to many community-level concerns, no new policy has been developed. The National Development Strategy (2016-2035) includes the government’s broader strategy for “sustained and inclusive economic growth” which includes mining. Part of this strategy includes reviewing and enforcing the Mining Act to improve sustainable mining resource management, introduce assessments with stakeholders on exploitation of mineral resources, carry out a survey to assess offshore mining, and encourage research.

Benefits for Stakeholders |

|

Government:

|

|

Landowners:

|

|

Mining Companies:

|

Fast-Track Mining Policy (COVID-19 Response)

The National Minerals Policy (2017 – 2021) gave the Ministry for Mines increased authority to, in conjunction with the Ministry of Infrastructure Development, decide the criteria to fast-track projects of national importance. This meant prioritising the quick approval of mining projects with little to no emphasis on proper consultation and comprehensive environmental protection. In June 2020, the Sogavare-led DCGA government announced a policy to fast-track mining activities in the country to bridge the revenue gap caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic. Government documents show how various committees came together to fast-track mining projects around the country, including the SIMCL Siruka Nickel Mining Project.

Case Study: Proposed Mineral Resources Bill 2025

In early 2025, the government quietly introduced the Mineral Resources Bill 2025 to Parliament. This Bill would replace the old Mining Act and expand government powers over mining decisions while reducing community rights even further.

The Bill itself would:

- Create a powerful Minerals Board without guaranteed landowner representation

- Allow mining licences to be issued without landowner consent

- Make it easier for government to compulsorily acquire land for mining

- Create appeals processes that are too technical and expensive for most communities to use

There was an earlier attempt to pass a Mines Bill that didn’t make it through the process. The caucus saw that the draft produced after consultations was substantially different from the draft presented at consultations. Without monitoring from communities involved in the consultations, this can happen.

The Mineral Resources Bill 2025 was a different bill that included some inputs from relevant stakeholders. According to process, the Bills and Legislation Committee called for public submissions, but there wasn’t a lot of community dialogue about the contents of the Bill even though the entire country would feel the impacts if passed.

The organisations behind this toolkit decided that more people should have their voices heard on the Bill and acted in two parts:

- Start public dialogue through the media

- Encourage individuals and CBOs to make submissions to the BLC with a submission guide and template

DSE (Development Services Exchange) coordinated groups to discuss the details of the Bill and ensure that CBOs’ voices would be heard in oral statements, and the submission guide made it easy for individuals and organisations to share their unique perspectives on what matters to them.

This response showed the power of organised communities and reminded people that the government is empowered to make decisions on behalf of them. If they have perspectives on what that should look like, they should have their voices heard.

When the government calls for public submissions, that’s your invitation to be heard. You don’t need to be a legal expert or a registered landowner. You are part of “the public” and the government is accountable to you. The submission guide showed that complex legal documents can be broken down so ordinary people can understand and respond to them.

While the Bill is still before Parliament, the BLC opened another call for submissions in August in response to the calls for more input from communities affected.

|

Key Lessons

|

Alex DeCiccio, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Building Power

Power is the ability to influence outcomes and is tempered by varying degrees of risk. It has many different sources. For example, a mining company derives most of its power from money. They can influence outcomes by paying individuals, both landowners and government officials, and often bear little risk because of the lack of enforcement of anti-corruption policy in the Solomon Islands and in their countries of registration. Communities also have power which is primarily from their ability to resist this and other divide-and-conquer tactics. This is also shaped by risk. Risk to those who stand up against powerful extractive companies, whether logging or mining, can face retaliatory legal action or violence at the hands of private or state security forces.

However, communities can increase their influence and decrease their risk by organising and growing their power. When communities are divided or uninformed, companies can claim they have social licence even when they don’t. But when communities organise and speak with one voice, it becomes much harder for companies to pretend they have genuine support.

Beware of Divide and Conquer Tactics

Mining companies often use divide-and-conquer tactics to weaken community resistance. This means they deliberately pit people against each other by offering money, jobs, or favours to certain individuals or groups, while others are left out. This creates distrust, jealousy, and conflict, making it harder for communities to unite and advocate for their shared interests.

Divided communities are easier to manipulate. If people are fighting among themselves, they are less likely to organise a strong, collective response.

How to Resist Divide-and-Conquer Tactics:

- Make decisions collectively. No one should negotiate alone. Agree as a group that all decisions affecting land must be made transparently and collectively to prevent companies from targeting individuals.

- Strengthen internal communication. Mining companies spread rumours and misinformation to create divisions. Regular community meetings and open discussions ensure that everyone has the same information, and no one is making decisions in secret.

- Support those targeted. If a company pressures or bribes someone, invite them into a supportive conversation and try not to blame them. If they are struggling financially, discuss community-led solutions rather than allowing the company to exploit their situation.

- Expose the company’s tactics. If you see the company trying to divide the community, call it out publicly. Naming their strategy can help take away its power.

- Create a community agreement. Develop a clear, written commitment that outlines shared principles on land protection. If everyone signs it, it becomes harder for a company to sway individuals.

- Build alliances beyond your group. Connect with other communities resisting mining. A larger network means companies can’t just move from one village to the next when they face resistance.

Unity is your greatest defense. When the community stays strong together, companies lose their ability to manipulate and exploit.

For individuals, community groups, and landowners in the Solomon Islands, organising is one of the most effective tools to push back against mining companies. Divide-and-conquer tactics like offering money, gifts, or promises to some individuals or groups in order to weaken collective resistance. When communities are strong and united, they are harder to manipulate, and they can make informed, strategic decisions about their land.

Community organising:

- Creates strength in numbers which grows your influence over elected officials by projecting a united front.

- Protects individuals and spreads out potential risk.

- Builds collective knowledge and can help the collective manage risk, learn from past efforts, and come up with creative strategies.

- Makes communities more resilient against manipulation tactics.

With a strong, accountable network of people, leaders are not as easily influenced by mining companies without facing scrutiny.

Case Study: Logging in Hograno, Isabel

The women leaders of the Konide customary land were watching their world get destroyed by logging companies. Their drinking water was contaminated, ancestral burial sites were destroyed, and traditional lands that fed their families were ruined. The women were shut out of decision making and left with little formal power. Logging companies only spoke to men, and male community leaders made deals without consulting women. This happened even though women and children suffered the most from the environmental damage. This divide-and-conquer strategy split the community and weakened resistance to harmful logging operations.

What They Did and Why

The women refused to accept being silenced. They organised multiple peaceful protests to directly challenge the logging operations, speaking out on the unfulfilled promises from companies and landowners. They spoke around their roles as mothers and caretakers, focusing on protecting clean water, ancestral sites, and their children’s futures. They also demanded legal accountability, pointing out that the Environment Act required proper development consent that was not being followed. Through persistent, organised action, they gained national media attention and brought outside pressure to bear on the situation.

|

Key Lessons

The women of Konide showed that when formal systems exclude you, you can still build real power through organisation, moral clarity, and strategic action. Their success offers a roadmap for any community facing similar exclusion from decisions about their land and future. |

Photo by Mike McCoy, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic

Guidance on Community Organising

There are many strategies for organising your community around shared concerns and goals. Often, this involved convening community leaders and mobilising community members for discussions on relevant issues.

Within community groups

Organising within community groups (tribes, organisations, churches) is the first step in building collective power. Some ideas for getting started include:

- Invite leaders and impacted individuals to share stories. Start by identifying the most appropriate people to lead such discussions (i.e. respected leaders, elders, or chiefs). Work together to create a space for those already affected to share their experiences of the impacts of mining in order to build community awareness and start important conversations.

- Use existing gatherings. Most kinship groups already gather for church events, tribal meetings, and cultural ceremonies. These may be natural spaces to have formal or informal discussions about mining and land protection. You may be in a position to encourage leaders who have seen the negative effects of mining to speak to their concerns at these gatherings.

- Take leaders to affected areas for first-hand learning. Leaders who have not yet experienced the impacts of mining may benefit from visiting people and areas that have borne the brunt of the damage. Experiencing it firsthand can be a powerful way to open their eyes to the risks.

Among Different Community Groups

Mining companies try to create divisions between different groups. To resist this, solidarity across community groups is essential.

- Identify like-minded groups. Start by exploring where other groups stand on mining. Work with churches, women’s groups, youth groups, and other networks to find allies.

- Strengthen existing relationships. Many people are already connected across kinship groups through marriage, trade, and shared land use. These relationships can be a foundation for further collaboration and organising. If someone in your group is married into another kinship group, ask them to help facilitate discussions about mining and its effects.

- Strategic gathering of groups. Holding joint meetings between different kinship groups can build trust and common ground. When trust is built, this can be an opportunity to establish common agreements with one another, so that companies cannot easily sway one group while others resist.

By organising within and across kinship groups, communities can control their own futures rather than letting mining companies dictate them. Together, people have the power to resist exploitation, protect their land, and hold decision-makers accountable.

Points of Intervention

There are many different moments and issues where communities can intervene in mining processes. Your choice depends on what’s happening in your area and what your community is ready to tackle.

Before Mining Starts

- Monitor permitting: build networks with other communities and monitor reconnaissance and permitting to warn others if/when they were not notified

- Stop reconnaissance permits: object when companies apply for permission to survey your land

- Refuse surface access: deny companies access to your land for prospecting

- Challenge environmental approvals: object to inadequate Environmental Impact Assessments

- Demand better consultation: insist on meaningful community involvement in decision-making

- Negotiate surface access agreements: get fair compensation and environmental protections

- Object to mining licence applications: submit formal objections during application processes

During Mining

- Monitor environmental compliance: track whether companies follow environmental rules

- Document violations: record when companies break laws or licence conditions

- Demand stop notices: request Ministry of Environment to halt illegal operations

- Seek compensation for damages: claim payment for environmental or livelihood losses

- Enforce surface access agreements: hold companies to their written commitments

- Report safety violations: alert authorities to dangerous working conditions

After Mining Ends

- Demand proper site rehabilitation: ensure companies restore damaged land

- Seek ongoing environmental monitoring :require long-term tracking of pollution

- Claim compensation for permanent damage: get payment for irreversible harm

- Document health impacts: record ongoing effects on community health

- Share lessons learned: help other communities avoid similar problems

Changing the System

- Reform mining laws: advocate for stronger legislation protecting communities

- Strengthen environmental regulations: push for tougher environmental standards

- Improve consultation processes: demand meaningful community participation requirements

- Reform royalty arrangements: seek fairer distribution of mining revenues

- Create protected areas: establish legal protection for sensitive environments

- Support alternative development: promote conservation or sustainable livelihoods

When Government Won’t Listen

- Use international human rights mechanisms: file complaints with UN bodies

- Engage home country oversight: target companies through their home country regulations

- Build international solidarity: connect with global movements against the extractives industry

- Use international media: get international attention on local struggles

- Engage development partners: pressure donors and international organisations

It’s Legal, but They Don’t have Social Licence

Understanding the Difference

The laws currently do not require genuine community support, so it’s important to distinguish between legal permits and social licensing.

Legal permits are the official documents from the Solomon Islands government that are granted under the terms of the law. A company can get these by meeting the technical requirements and the minimum standards set out in law, for example the Mining Act.

Social licensing is the genuine approval and ongoing trust of affected communities. This means that real consultation with the community has taken place before any decisions, and the community can withdraw support if promises are broken.

This is similar to the international standard of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC). This standard means communities have the right to say no to projects affecting their land. However, this standard is not protected in the Solomon Islands at the moment.

The Mining Act only requires “consultation” and “informing” landowners, and under the law, companies can tick these boxes without getting genuine consent. The law allows the Minister to even compulsorily acquire land even if communities object.

Under the law, a company can have the legal permits but no social licence. In this case, a powerful advocacy strategy would point to the gap in the laws and the lack of social licence, saying that the law does not protect our Free, Prior, and Informed Consent and that the company does not have the community’s social licence. This can be demonstrated by showing:

- Inadequate consultation

- Community opposition

- Broken promises

- Lack of genuine consent

Know Your Rights

What is Protected in Existing Law

Understanding your legal rights is the first step to protecting your interests when mining companies approach your community. The law does give landowners and communities some protections and entitlements, but it’s important to know both what you’re entitled to and where the law’s limitations are.

Financial Rights

Royalty Payments (Section 45, Mines and Minerals Amendment Act 2014)

- Mining companies must pay 3% royalty of the gross value of minerals

- Landowners get 40% of this royalty

- Government gets 50%

- Provincial Government gets 10%

Surface Access Fees (Mines and Minerals Act Section 17)

- Companies must pay you for access to your land

- The Mining Board helps determine these fees

- You have the right to negotiate these payments

Compensation (Mining Board Functions)

- You are entitled to compensation for any damage

- The Mining Board assists in determining compensation amounts

Trust Fund (Mining Board Functions)

- The Mining Board must establish trust funds for landowners and landholding groups

- This protects your financial interests

Information Rights

Right to Be Informed (Mining Board Functions)

- The Mining Board must inform landowners about operations that will affect them

- You should know what activities will happen on your land

- Companies cannot operate without telling affected communities

Environmental Rights

Environmental Impact Assessment Required (Environmental Act 1998)

- No mining can happen without environmental approval

- Companies must produce environmental impact reports

- You have the right to participate in public hearings about these reports

Appeal Rights (Environmental Act 1998 Part III)

- You can appeal environmental decisions within 30 days

- Appeals go to the Environment Advisory Committee first

- You can appeal to the Minister if still not satisfied

Consultation and Negotiation Rights

Surface Access Agreements (Mining Board Functions)

- Companies must negotiate surface access agreements with you

- The Mining Board assists in these negotiations

- You are not required to give consent automatically

Legal Support (National Mineral Policy 2017-2021 – expired)

- The National Mineral Policy promises access to legal services for landowners

- You should get transparency on all agreements

- Traditional authority should be used for land identification

Important Limitations to Know

Government Can Override Your Rights (Section 33, Mines and Minerals Act & Land and Titles Act)

- If you refuse mining, the Minister can direct compulsory acquisition of your land

- The Constitution allows this for “public benefit” (Section 9, Constitution)

- You would receive compensation but could lose your land

Minerals Belong to Government (Section 2, Mines and Minerals Act)

- All minerals under your land belong to “the people and Government of Solomon Islands”

- The Government has exclusive rights to develop mineral resources

Remember: These rights exist on paper, but you may need to hold duty bearers accountable to make sure they are respected. The law also gives the Solomon Islands government power to argue to take the land even if you say no. Understanding your rights is the first step to protecting your interests and making informed decisions.

Photo by whl.travel, licenced under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Advocacy Pathways

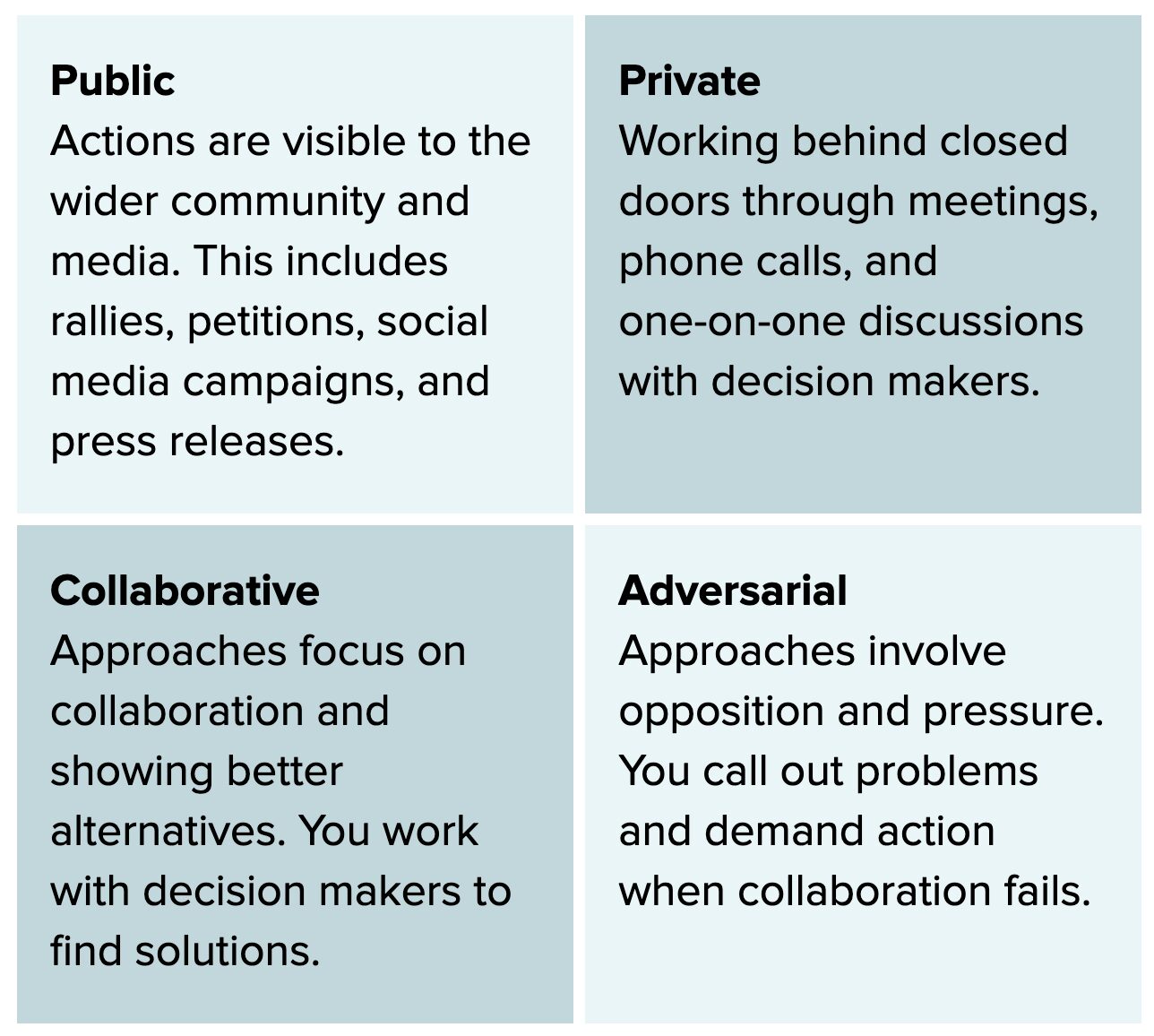

Once you’ve identified your point of intervention, it’s important to choose an effective strategy. Your approach can be guided by:

- The willingness of decision makers to act

- Capacity of the community to take action

- Time sensitivity/urgency

- Lessons from prior actions

- Assessed risk

These factors shape whether you want a more public approach or a private one. They also decide whether you are more positive and collaborative or more adversarial and oppositional. Sometimes, these approaches change as more information is learned.

Case Study: Rennell Island Bauxite Mining

Sometimes stopping harmful activities in the extractives industry requires a long campaign using different tactics over time. The communities of Rennell Island show us how to start with collaborative approaches and escalate strategically when those fail. Their fight against bauxite mining demonstrates that persistence, documentation, and community unity can eventually overcome even well-established mining operations.

Their Situation

Communities on Rennell Island faced bauxite mining that began around 2011 and caused serious environmental damage. The mining operation was badly managed from the start. Even the Solomon Islands’ highest mining official admitted it was “messed up” and done “in haste.” A major oil spill in February 2019 dumped 300 tonnes of oil and caused $50 million in losses. Companies owed millions in unpaid taxes and royalties, with only 67 of 100 shipments properly paid for. Communities had mixed capacity to respond, with some groups organised while others were divided by mining company tactics. The situation was urgent because mining was causing immediate damage, but speaking out risked retaliation.

What They Did and Why

The communities chose their approach based on the willingness of decision makers to act, their own capacity to organise, time sensitivity, lessons from past actions, and their assessment of risk.

They started with private collaboration. Community leaders and officials tried working within the system first. The former Prime Minister acknowledged that “the Solomon Islands have not benefited from the Rennell mining operations.” They raised concerns through proper channels, hoping authorities would respond to reasonable requests.

They moved to public collaboration when private efforts stalled. Communities formed organisations like the West Rennell Land and Resources Owners Association and created a dedicated mining taskforce to seek better arrangements. They documented environmental damage systematically and educated people about alternatives to destructive mining.

They escalated to public confrontation when collaboration failed. After other approaches proved ineffective, 250 out of 266 landowners formally revoked their Surface Access Agreement with the mining company. The Provincial Premier publicly stated plans to cancel mining operations, saying “people have been losers in their land since the operations started.”

They pursued legal action for accountability. In February 2025, the people of Rennell Island filed a legal case against the company for compensation over environmental damage, ensuring there would be consequences for the harm caused.

|

Key Lessons

The Rennell Island communities proved that strategic escalation and sustained pressure can stop even established mining operations, though the cost of waiting too long to act can be severe environmental damage that takes years to repair. |

Photo by Jenny Scott, licenced under CC BY-NC 2.0

Tactics

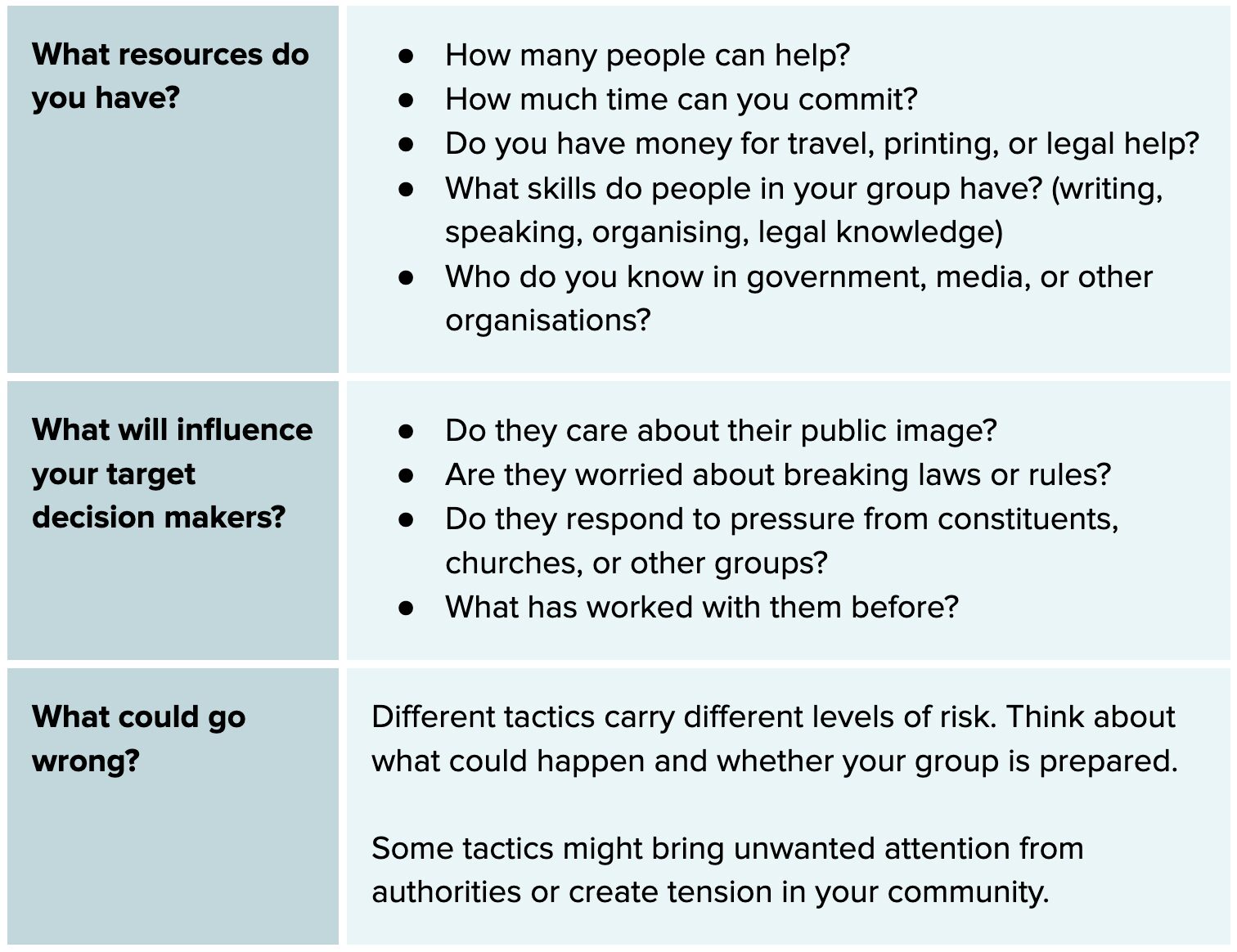

Once you know who you want to influence and what pathway makes sense, you need to pick the right tactics.

Start by asking these questions:

Example Tactics

Documenting and Monitoring

|

Take photos of damage. Keep records of meetings and promises. Share updates on social media or with other communities. This creates evidence and keeps people informed.

|

Letters and Submissions

|

Write to MPs, the Minister of Mines, the Mining Board, or directly to companies. Submit comments on new policies or environmental impact assessments. You can also write to UN human rights bodies or company shareholders.

|

Petitions

|

Collect signatures to show how many people share your concerns. This demonstrates community support and can be presented to decision makers.

|

Media Campaigns

|

Work with journalists to tell your story. Use radio, newspapers, and social media to raise awareness and put public pressure on decision makers.

|

Speaking up in Meetings

|

Attend public consultations. Ask hard questions. If you think your concerns aren’t being taken seriously, consider making your comments public through media.

|

Meeting with Decision Makers

|

Request meetings with MPs, provincial leaders, or government officials. Come prepared with clear asks and evidence of your concerns.

|

Protests and Direct Action

|

Organise peaceful gatherings to show public concern. Always consider safety and legal risks beforehand.

|

Legal Action

|

File court cases or formal complaints. This requires legal help and can be expensive. Contact the Public Solicitor’s office for advice about your options.

|

Case Study: Start Somewhere

It can feel overwhelming at times to feel small compared to the power of the government and big mining companies. However, sometimes your interests and their interests align. For example, a community wrote a letter to a logging company asking them to remove logs that were blocking a road. The company responded by removing the logs and announcing they would leave the area entirely. Start somewhere with tactics that you have capacity for, and escalate only as needed.

|

Remember, you don’t have to use all these tactics. Pick the ones that match your resources, your target, and the level of risk your community is comfortable with. Often, starting with gentler approaches and building up works best. |

Using International Human Rights Mechanisms

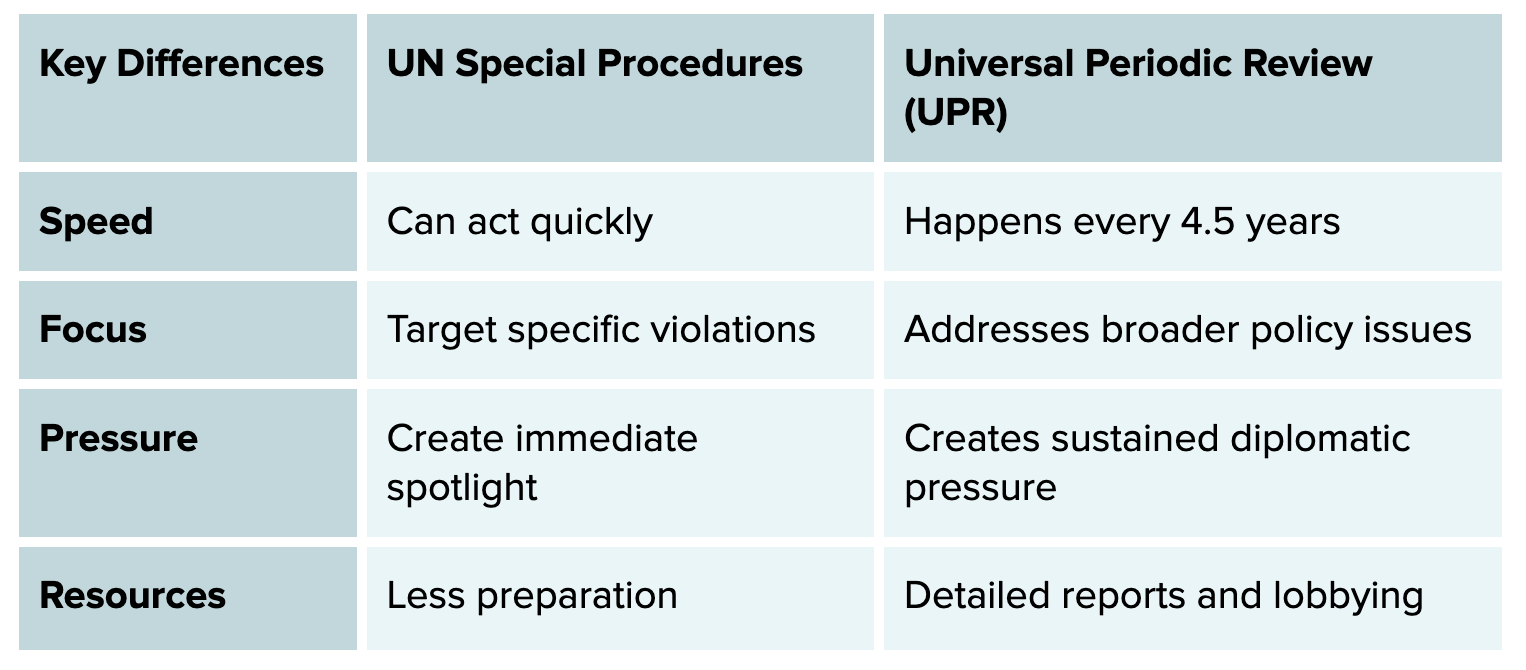

When advocacy isn’t working and your government won’t listen, international human rights mechanisms can add pressure and legitimacy to your campaign. Here are two powerful options:

- UN Special Procedures. Independent human rights experts who investigate violations and pressure governments and companies to act.

- Universal Periodic Review (UPR). Every 4.5 years, UN countries review each other’s human rights record and make recommendations.

These tools can create international attention and pressure from other countries that is harder to ignore than local complaints alone.

UN Special Procedures

These are independent human rights experts appointed by the UN Human Rights Council to investigate and report on specific human rights issues. These experts work independently from governments and can act quickly when violations occur.

When to use it:

- For urgent situations needing immediate attention

- When companies are violating human rights

- To get international media coverage

- When you need expert backing for your case

- When domestic legal options have failed or don’t exist

How it works: You submit a complaint describing what happened, who’s responsible, and what action you want. The experts can then: write official letters to your government demanding answers; visit your area to investigate firsthand; make public statements calling for action; and/ or issue reports that get international attention.

Specifically, the Working Group on Business and Human Rights addresses corporate accountability in industries like mining. They can pressure both governments and companies to respect community rights and follow international standards.

Universal Periodic Review (UPR)

Every 4.5 years, UN countries review each other’s human rights record and make recommendations. This peer-to-peer process creates diplomatic pressure because countries care about their international reputation. The recommendations made to each country create a public record of their position on human rights issues.

When to use it:

- For broader policy changes you want

- When you have time to plan (reviews happen on schedule)

- To get multiple countries pressuring your government

- For long-term systemic issues that need sustained attention

How it works: Civil society organisations submit reports about human rights issues in your country. These reports inform other countries, who then make official recommendations to your government during the review process.

Tips for Success:

- Get help from human rights organisations who know the processes

- Document everything with dates, names, and evidence

- Connect with other communities facing similar issues

- Be prepared for potential backlash and have support systems ready

Building Power for Tactics

These tactics get stronger when there is more people power behind them. Think about the difference in impact between a petition signed by 10 people versus 1,000 people, or two people having a meeting with a decision maker versus filling their week with meetings of community members voicing their concerns.

The real goal of any tactic is not just to complete an action, but to explore who else is impacted and bring them into your movement. Every tactic should be designed as a way to get more people involved. When you organise a petition, you are not just collecting signatures. You are having conversations about why the issue matters and inviting people to take the next step.

Think Beyond Your Immediate Community

Mining and logging affect many different groups in different ways. Fishers worry about water pollution. Farmers fear soil contamination. Parents are concerned about their children’s health. Shop owners see businesses hurt when communities are divided. Church leaders want to protect creation. Each group might care for different reasons, but they all have a stake in the outcome. Your job is to help them see how your fight connects to their concerns.

Use Tactics to Build Your Movement |

|

Documenting and sharing like uploading pictures and videos of environmental damage creates visual stories that help others understand what is at stake. Each person who shares content becomes part of telling that story and may be willing to take bigger actions later.

|

|

Mobilisation events like Anti-corruption Day (9th December) events create opportunities for different groups to see they are not alone. When farmers, fishers, church members, women’s groups, and youth organisations all show up to the same events, they realise they have more power together than any of them has alone.

|

|

Community meetings should always end with clear ways for people to get more involved. Have sign-up sheets for different types of support: hosting future meetings, helping with transport, speaking at public events, or reaching out to family members in other villages.

|

|

Petitions work best when they become conversations, not just signature collection. Train petition carriers to spend time talking with people about the issues, listening to their concerns, and finding out what other problems they face that might connect to your campaign. |

Remember, every person who joins your movement brings their own networks of family, friends, and community connections. A fisher might bring their fishing association. A church member might speak to their congregation. A women’s group leader might connect you with women’s groups on other islands. Think of each new person as a bridge to even more people who care about protecting land, water, and community wellbeing.

The strongest movements are built around many people taking on different roles, contributing different skills, and reaching different parts of the community. Use every tactic as a chance to find these people, develop their leadership, and expand your power to create the changes your community needs.

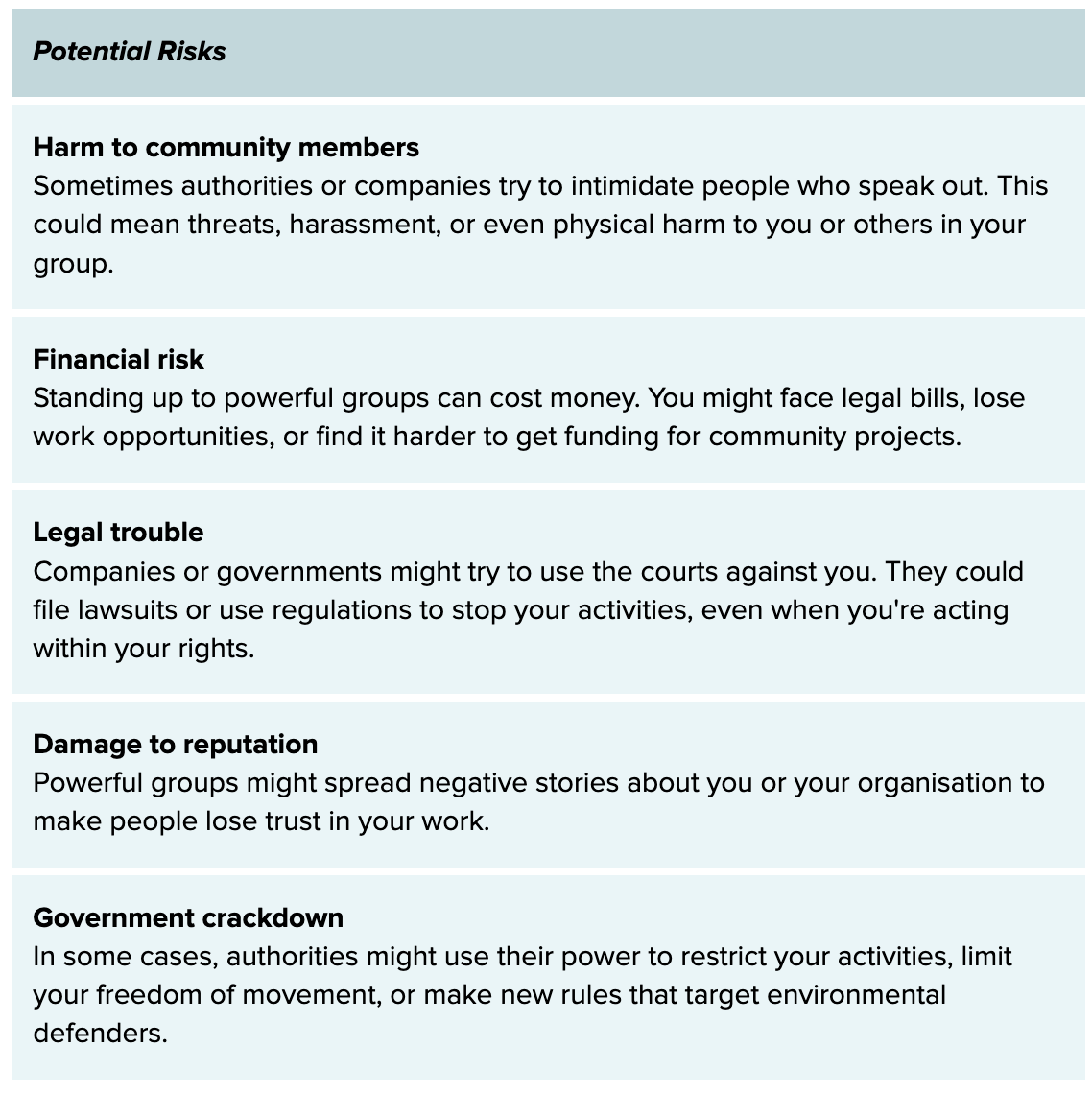

Understanding the Risks

When you stand up for your community and challenge powerful companies or government decisions, there can be pushback. These groups might try to stop your work or make things difficult for you. It’s important to know about these risks before you start and plan how to stay safe.

You can take steps to protect yourself and your community. For example, when challenging mining or logging companies, work with other groups and organisations. Build a network of supporters including lawyers, journalists, and other communities facing similar issues. Document everything you do and keep good records. Share information widely so that many people know about your work. This makes it harder for companies to target you quietly.

Always follow legal processes and know your rights. Get legal advice when you can. Stay connected with human rights organisations who can help if problems arise.

Your Rights as an Environmental Human Rights Defender

Environmental human rights defenders are people who work to protect and promote human rights related to the environment. This includes anyone fighting to keep their land, water, and air clean and safe for their community.

As an environmental human rights defender, you have specific rights under international law. You have the right to speak out about environmental issues, to organise peaceful protests, and to access information about projects that affect your environment. You also have the right to participate in decisions that impact your community and environment. These rights are protected even when your work challenges powerful interests.

Further Information

Public Solicitor’s Office

They have further legal information and can potentially support via their Landowners’ Advocacy and Legal Support Unit (LALSU)

Honiara: (677) 28405 / 28406 / 22348 / 28404

Gizo: (677) 60682

Auki: (677) 40008 / 40006

Kirakira: (677) 50153

Lata: (677) 53004

Munda: (677) 62104

For Telekom A and B Mobile users, dial *776# to access free legal information. No mobile data needed. Select “Environmental Law” for mining-specific concerns.

Solomon Islands Environmental Law Association (SIELA)

+677 76 95597

solomonislandsenvironmentallaw@gmail.com

Accountability Counsel

Contact: https://www.accountabilitycounsel.org/contact-us/

More information:

https://www.accountabilitycounsel.org/

An international NGO supporting communities to use investors’ dispute mechanisms