Executive Summary

One third of all women and girls worldwide face an ongoing epidemic of gender-based violence (GBV). Gender discrimination in the form of GBV, bias/ stereotyping, myths, customary practices, patriarchy, and toxic masculinity shapes societal expectations about women’s and girls’ continued subordination. A clear and direct line can be drawn between gender discrimination and violence, and this report seeks to elucidate this connection by providing an international and regional overview of cases and legislation that have been found to violate human rights norms, and then by focusing our analysis on Pacific Island Countries, where women and girls face the highest rates of violence globally, on average. The analysis shows how the perpetuation of bias/stereotyping that leads to violence is not just confined to the domestic sphere or specific communities, but pervades each and every institution, including those charged with upholding justice.

Part I of the report considers key concepts of gender discrimination and explores three case studies – Fiji, where women’s traditional obligations in the domestic sphere lead to domestic violence because of societal conceptions of “ideal behaviour” for women; the practice of “bride price” in Vanuatu, a widespread customary practice where a groom pays money or goods to his bride’s family as part of their marriage; and finally, sorcery and witchcraft in Papua New Guinea, which is an all too convenient excuse for violence and even murder of elderly women who are economically dependant on their tribe, or a way to silence and control intimate partners.

Part II of the report conducts an exhaustive analysis on major international and regional human rights instruments and their prohibitions on discrimination against women, including: the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Convention Against Torture, and the Beijing Platform for Action 1995. In the regional context are the Inter- American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment and Eradication of Violence against Women (the Convention of Belém do Pará), Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence 2011 (Istanbul Convention), and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights and its 2003 Protocol on the Rights of Women in Africa (the Maputo Protocol). All these instruments and related jurisprudence brought before respective regional courts speak to the nuances related to gender stereotyping/bias and violence.

Part II further analyses gender stereotyping, bias, myths and customary practices through the lens of international and regional human rights instruments, by examining formative legal cases and legislation. For example, in Vertido v The Philippines, the CEDAW Committee found that the Court violated CEDAW because it sought to impose a duty upon the rape victim to prove resistance. More importantly, the CEDAW Committee made clear that there is no “ideal” rape victim and warned the Court to take caution regarding their preconceived notions of what women should be or want. However, sometimes the international bodies themselves overlook the stereotypes courts relied upon in making their decisions. In L.N.P v Argentine Republic, The Human Rights Committee missed an opportunity to dispel gender myths about when consent can be withheld and sexual inexperience as a precondition for a rape conviction.

In contrast, the regional framework of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights specifically recognises gender stereotyping as a cause of violence against women. This finding was made in the context of Mexico’s continued lack of response to the death and disappearances of women in Ciudad Juárez, which relied on stereotyped conceptions of why the women went missing. In the context of parental leave, the European Court of Human Rights found that stereotyped perceptions of men as breadwinners and women as caretakers could not justify differential treatment and that such stereotypes undermine women’s careers. In addition to judicial decisions being replete with gender bias, the African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights has also found legislation upholding traditions and customary practices to be discriminatory against women and children. What this snapshot reveals is that gender stereotypes, bias, myths and customary practices are globally pervasive and that the institutions charged with upholding justice can undermine the notion of justice through biased decision-making.

Part II concludes with a study of pioneering case law and legislation that target manifestations of gender bias that lead to violence against women from national jurisdictions including: Canada, where the use of the defence of “implied consent” was overturned; Fiji, where the Chief Magistrate issued directives as to correct the misapplication of first-time offender status and caution against requiring complainants to attend joint counselling with offenders; Mexico, where the Supreme Court published a protocol that explains how international human rights treaties are to be implemented as binding law by domestic courts; Namibia, which codified the criminalisation of rape within marriage; Australia and New Zealand, both of which instituted legislation to provide leave from employment for victims of domestic violence; and the United Kingdom, where a rule was issued preventing advertising from including gender stereotypes likely to cause harm.

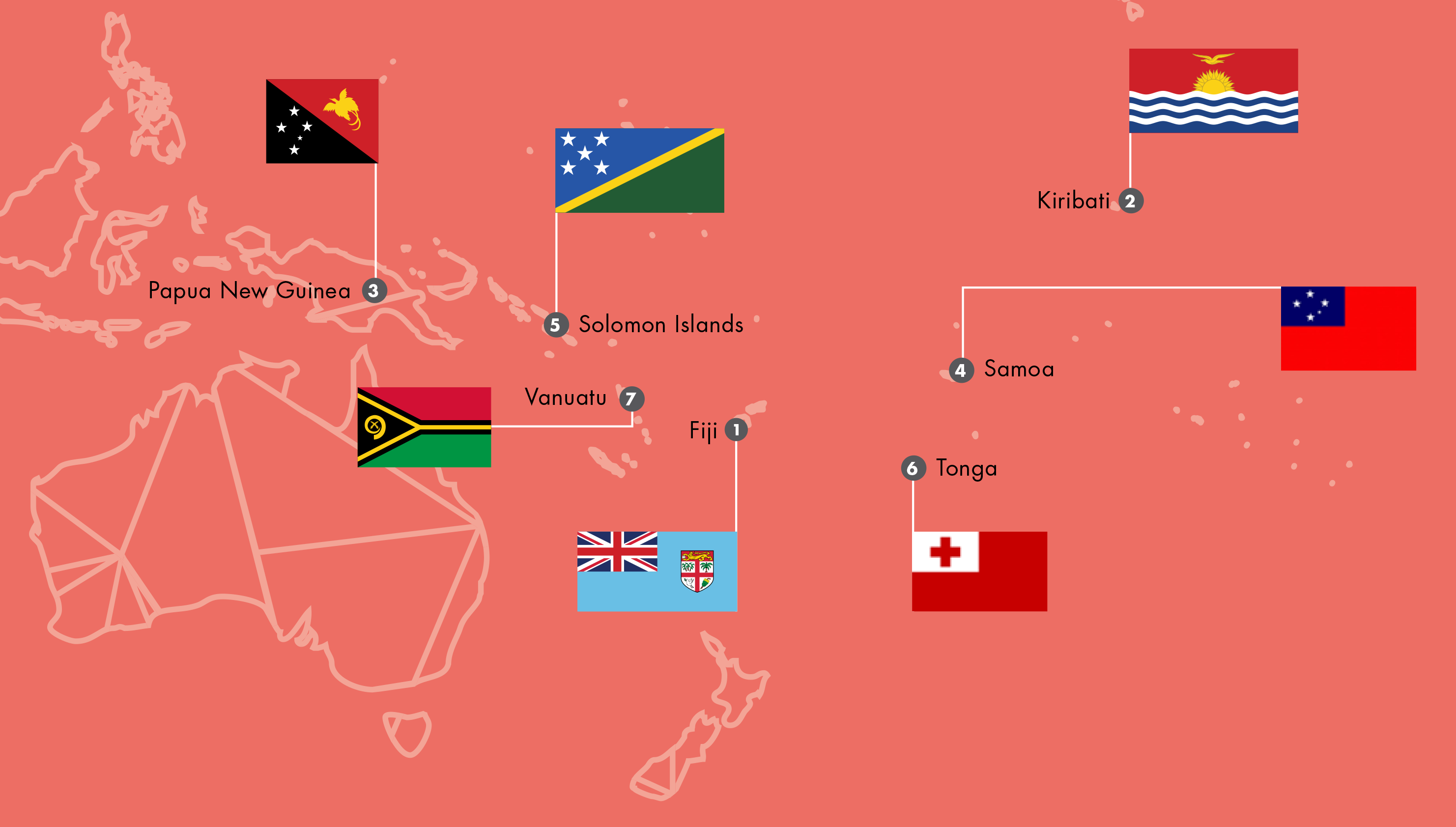

Part III, comprising the bulk of the report, explores the scope of gender-based violence against women and girls in the Pacific Island Region and provides in-depth analyses of cases from seven Commonwealth countries in the Pacific Islands – Fiji, Vanuatu, Tonga, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Papua New Guinea, and Kiribati. The extent of GBV in the Pacific is unprecedented – across the region, 60%-80% of women and girls face violence across the spectrum of intimate and non-intimate partner violence. The rate of violence is shaped by many factors, from socio-economic circumstances and poor enforcement to differences in cultural practices, perceived gender roles, and gender stereotypes. These rates are also compounded by other intersecting discriminatory factors, such as disability, sexual orientation, and gender identity.

The analyses of cases from across the Pacific Island Region focus on how customary forms of reconciliation, gender stereotypes, rape myths and other factors are considered in sentence mitigation. This focus resulted from a pilot analysis of randomly selected cases conducted by ICAAD that indicated that gender bias reduced the sentences of perpetrators in 52% of GBV cases across the region. An overarching review of cases from Fiji across an 18-year period highlights the importance of monitoring and evaluating sentencing decisions to assess transparency, consistency, and accountability. This overarching analysis reveals key information in relation to access to justice in courts, including the application of first-time offender status, inclusion of medical reports, age of victims, victim anonymity, and gender bias resulting in reduced sentences.

Part III concludes with an in-depth analyses of GBVAW cases in seven Pacific Island Countries, assessing the impact of gender-bias and stereotyping on jurisprudence, customary reconciliation practices, factors privileging perpetrators (victim-blaming, provocation, rape myths, alcohol as an excuse) and the operation of parallel state and customary legal systems.